Business & Education

Nazi Germany to Danish Navy: “You sank my battleship”

This article is more than 9 years old.

Patriotic disobediance by a Danish vice admiral rendered 70 percent of the Danish fleet unusable

Two of the soldiers pictured here on the morning of 9 April 1940 were among the 16 killed in the two-hour war with Germany (photo: Valentinian)

German forces crossed the border into neutral Denmark on the morning of 9 April 1940, meaning the previous year’s non-aggression pact had gone the way of so many others the Nazi government made. In a remarkably gentle invasion, troops crossed easily into southern Jutland. Shortly afterwards, un-armoured German ships boldly docked in Copenhagen and began disembarking soldiers and equipment. The only resistance came in isolated pockets: – skirmishes in Jutland and outside the final bastion of Danish sovereignty, Amalienborg Palace, which only succeeded in prolonging Denmark’s official war with Germany to a grand total of two hours, at the cost of 16 soldiers killed in action.

As with the Netherlands, the fatal combination of flat geography and severely limited armed forces meant that resistance to the notoriously efficient German war machine was generally considered to be a pointless exercise.

The leisurely invasion

Although the government had in fact been forewarned by its intelligence of the impending invasion, it either failed or decided not to act. Combined with effective leafleting propaganda that threatened an aerial bombardment of Copenhagen, the fate of Denmark was quickly sealed.

The amicable conclusion allied with the Nazi’s reverence for Germanic Scandinavians meant that Denmark got off pretty lightly when the Germans came to rolling out their imperial designs, claiming they would ¨respect Danish sovereignty and territorial integrity, as well as neutrality¨. In practice this fine example of Orwellian doublespeak meant that the Danish government was as free to govern itself only as far as it is possible for the client state of an imperialist superpower to be.

Naturally the armed forces were largely demobilised; however, the navy’s ships were still staffed by Danish sailors and even performed minesweeping operations, while the army was allowed to maintain 2,200 men and 1,100 auxiliary troops until August 1943. In keeping with the friendly accord, the Germans largely stopped short of actually acquiring the Danish war-making apparatus, such as it was, but still demanded 12 torpedo boats in February 1941, which the Danish government agreed to, although only six were eventually delivered.

Best regards; Best in charge

By August 1943, resistance to the Germans became so blatant that they were left with no option but to declare martial law and dissolve the puppet regime. The troubled relationship had been souring for some time, with the population becoming steadily less accepting of the Germans, who complained that they found the population to be cold and distant. Although the Danish government had tried to prevent violence and sabotage, by late 1942 Germany declared Denmark to be ‘enemy territory’ for the first time.

In late 1942, a diplomatic crisis arose between King Christian X – who had been left in place as head of state – and Hitler himself. Following a long and flattering telegram congratulating the king on his birthday, Hitler was infuriated to be snubbed by the curt reply: ¨Giving my best thanks. King Christian¨. The response was a swift crackdown and the arrival of a new plenipotentiary (effective leader): Dr Werner Best.

Best allowed an election in March 1943 which, combined with a growing feeling of optimism that Germany would be defeated, led to widespread strikes and protests throughout the summer of 1943, culminating in a draconian ultimatum to the Danish government that sought to hammer the final few pieces of the totalitarian structure into place. Amongst other demands, the Germans required the government to ban public assemblies and strikes, to introduce a curfew, and to establish the death penalty for sabotage. The government refused, and martial law was declared on 29 August 1943.

A hero in their hour of need

Knowing that the navy would now be fair game to the Germans, and useful to their war effort, one man acted quickly and decisively this time. Vice-Admiral Aage Helgesen Vedel had resolved back in 1941 that no more of his fleet would be allowed to fall into the hands of the enemy, and he secretly ordered the captains under his command to prepare scuttling charges. As the political standoff intensified leading up to the deadline of the ultimatum, the charges were checked and the 2,000 men at the Holmen naval facility put on alert against a potential German attack.

When Vedel told the defence minister, Søren Brorsen, of his plans, the latter disagreed and instead instructed the order to be issued that the navy would be handed over intact, causing a crisis of conscience for Vedel, who was caught between obeying orders and performing his patriotic duty. His solution was to broadcast Brorsen’s orders to the respective captains with the added caveat: “In the circumstances, the ships can be sunk.”

Safari: subterfuge, scuttle, sink

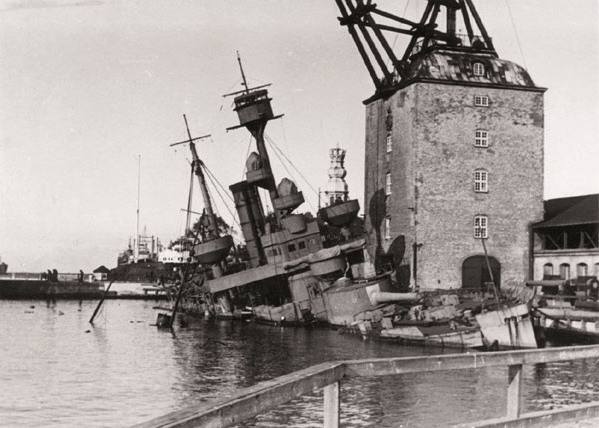

The anticipated German attack, ‘Operation Safari’, came on the morning of 29 August, but the Danish sentry guarding the bridge to the Holmen base conveniently lost the handle that lowered the bridge, delaying the 500 German soldiers long enough for 32 ships to be sunk where they lay. Four more ships reached the safety of neutral Sweden, while 14 were captured.

Skirmishes with the occupying German forces here and in military installations across the country left 23 Danes dead, and the Germans were ultimately able to salvage and reuse 15 of the scuttled ships for residential and educational use. However, none of the Danish submarines were used again.

Respect from a German peer

In a speech to the sailors after the actions, the head of the inshore fleet, Commander Paul Ipsen, said: “The Danish Navy has sunk with honour; long live the Danish Navy.” Two hours later the commander of the German naval forces in Denmark, Admiral Hans-Heinrich Wurmbach, paid his respect towards his captive Danish counterpart, Vice Admiral Vedel, with the words: “We’ve both done our duty.”

Vedel was briefly detained for his efforts, but afterwards became a member of the government, while remaining in close contact with the resistance movement and helping to co-ordinate the illegal transfer of arms from Sweden.