News

When life’s this good, who needs the Metaverse, chorus Danes in their condemnation of virtual worlds

This article is more than 2 years old.

Only the Irish hate it more, according to a new study, but there’s a good reason why people in advanced societies tend to shun such technology, according to an expert

Another Saturday night on your own (photo: Flickr/NASA/Bill Ingalls)

Putting on a pair of virtual reality (VR) goggles and experiencing augmented reality (AR), investing in NFT art, and building virtual worlds – it hardly beats the joys of hygge in company, framing your three-year-old’s latest masterpiece, and fixing the roof of your summerhouse, does it?

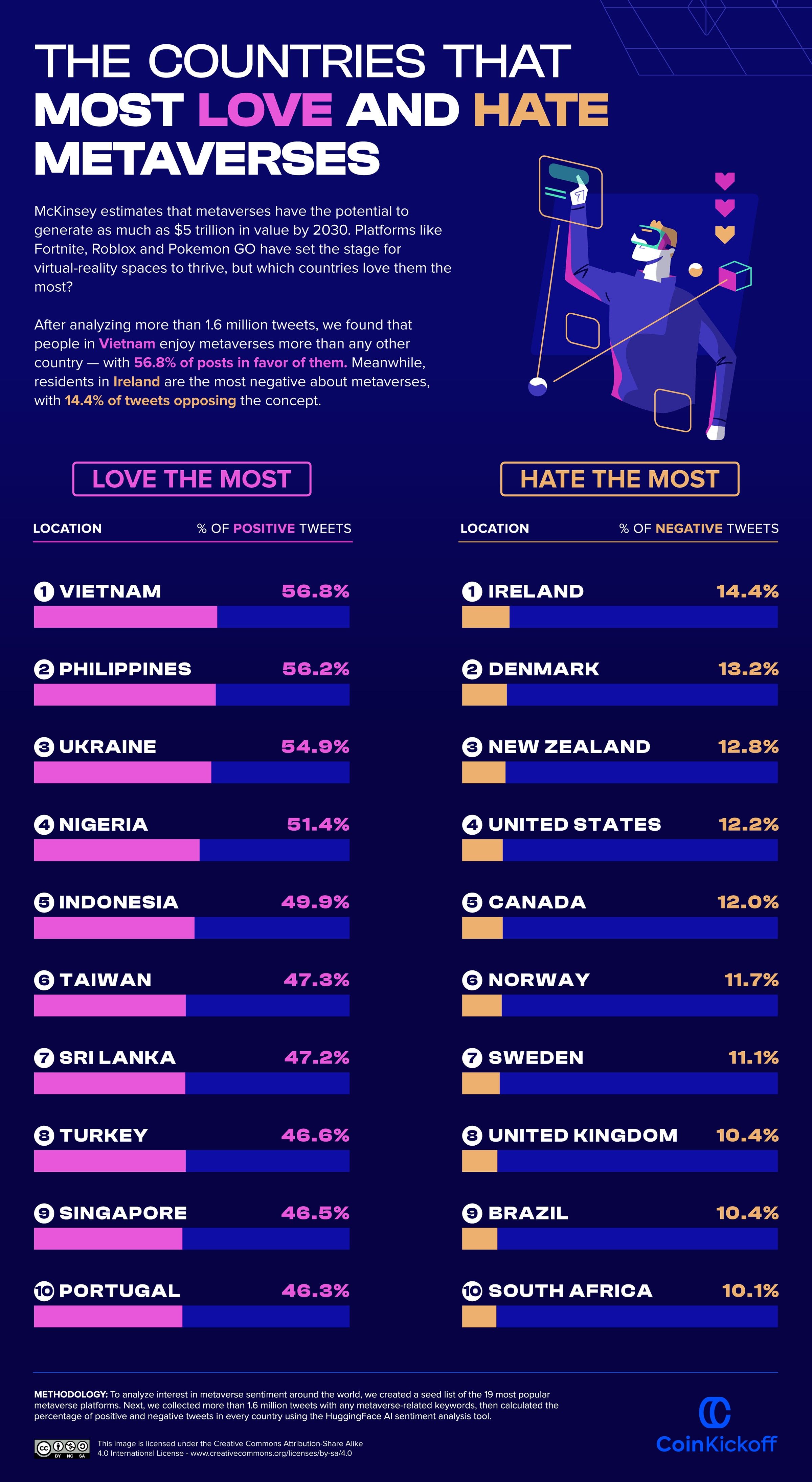

Well, according to extensive research carried out by Coin Kickoff, the Danes are the second most likely nationality to hate the Metaverse, trailing only the Irish, who have no feckin’ time for that shite either.

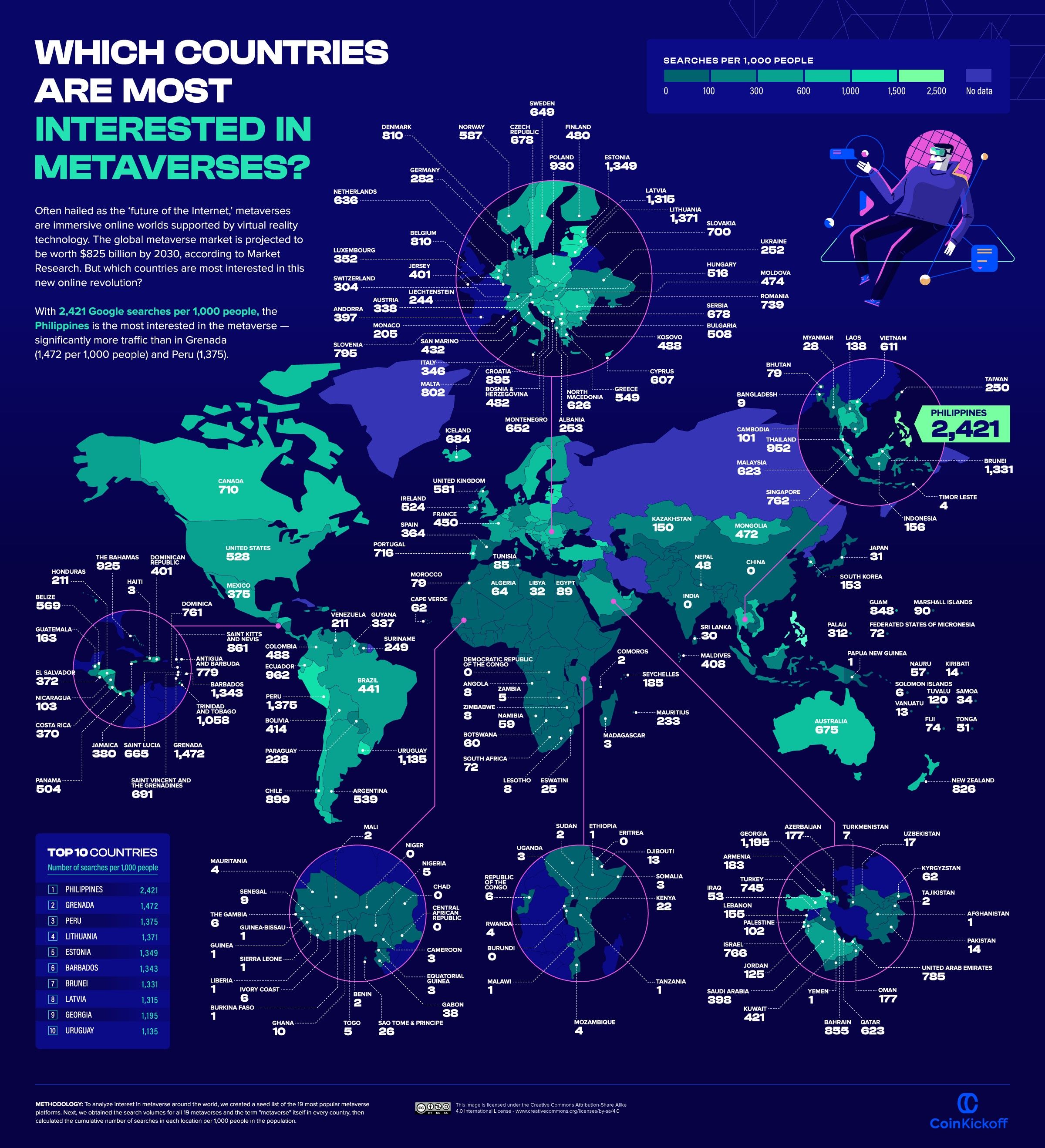

Coin Kickoff reached its conclusions by using the AI sentiment analysis tool HuggingFace to assess 1.6 million tweets, 19 of the world’s most popular metaverses, and Google search volumes for metaverse-related keywords in 192 countries.

Huge fondness in Southeast Asia

Trailing Ireland and Denmark, New Zealand, the US, Canada, Norway, Sweden, the UK, Brazil and South Africa completed the top ten countries most likely to hate the Metaverse – a list, with the exception of Brazil, dominated by Anglophone and Scandinavian countries.

The top ten countries most likely to love the Metaverse are Vietnam, Philippines, Ukraine, Nigeria, Indonesia, Taiwan, Sri Lanka, Turkey, Singapore and Portugal.

For example, 56.8 percent of tweets made by Vietnamese people about the Metaverse are in favour of it. In the Philippines there are a world-leading 2,421 Google searches for the Metaverse for every 1,000 people.

At the other end of the spectrum, 14.4 percent of tweets made by Irish people contain negative sentiment, closely followed by the Danes with 13.2 percent.

A question of contentment

So why is the Metaverse so popular in Southeast Asia and unpopular in Northern Europe? According to ART[XR].com founder Eric Prince – who has 25 years of experience developing online, mobile games and immersive 3D web VR/AR/XR technologies – it is primarily a question of contentment.

The Danes are frequent winners of the world’s happiest people, and this is not a good fit for the Metaverse, he contended from his art gallery in Copenhagen, where he is working on bridging fine arts and digital platforms to help usher in what is being called the future of the internet.

“The Danes may be experiencing far too much real utopian society to go looking for a virtual utopian replacement. Simply, life is good in Denmark,” he concluded.

In contrast, Vietnamese and Filipino fans of the Metaverse might be looking for escapism, he suggested – poignantly Ukraine is one of only two non-Asian countries in the top ten who love it.

A matter of sophistication

Furthermore, the Metaverse is currently lacking in sophistication if the “designed-by-committee nightmarish safety manual look” of Horizon Worlds is anything to go by”, pointed out Prince – again making it a better fit for tastes in Vietnam and the Philippines than Denmark and its northern European neighbours.

“The first designs of the Metaverse have been very cartoony and appealing to a mass consumption or unsophisticated aesthetic taste. This is not being overly critical, more a direct observation backed by early success in the Metaverse by companies like Roblox, which was specifically designed for kids,” explained Prince.

“In contrast, poorer countries like the Philippines seem to be engaging generously with the Metaverse and how it is currently being presented. Maybe these people are more optimistic and thankful, or maybe the candy-deliverable cartoony palette is more appealing than their reality.”

Value increasing by the day

According to Gartner, 25 percent of the planet’s population will be spending at least an hour per day in the Metaverse by 2026 – as it becomes a mecca for gamers – while McKinsey predicts the sector could be generating as much as 5 trillion US dollars in value by 2030.

Facebook (remember that it changed its name to Meta in 2021, but nobody cares) has seen a recent downturn in interest in its new venture Horizon Worlds, which it launched in 2021 after acquiring the VR platform Oculus for 2 billion US dollars seven years earlier.

Subscriptions to Horizon Worlds were initially brisk, reaching 300,000 active users by February 2022. But since then, numbers have fallen by 50 percent. The company’s share price toppled by 70 percent in 2022.