Business & Education

Tivoli’s murky past: Reckless showmanship and kids in cages

This article is more than 3 years old.

There has certainly been plenty of weirdness, to go alongside the wonderful events, at the gardens over the course of its nearly 180-year history

Soaring into the sky in 1904: nobody’s been higher since (all photos: Københavns Kommune)

When Tivoli opened for the first time in 1843, Copenhageners were able to leave behind their cramped and smelly city and step into a magical world of entertainment. A look back at Tivoli’s history reveals entertainment that seems hard to imagine today: from highly flammable hot air balloon rides to children exhibited in cages.

Its highest ever ride

The mid-1800s was a time of innovation and adventure during which hot air ballooning captured the people’s imagination. In Copenhagen, Balloon Captain Lauritz Johansen used the Tivoli Gardens for his thrilling ascents.

Accompanied by music from Tivoli’s orchestra, he would hang out of the basket and salute onlookers as the balloon lifted into the air. Sometimes he even attached fireworks to the basket, which he detonated once the balloon was airborne to the delight of the crowds below.

In 1891, Tivoli took the enthusiasm for ballooning one step further and created a breathtaking ride for paying guests. Johansen took over as captain of the enormous hot air balloon ‘Montebello’. The balloon was tethered to the ground, but when the ropes were loosened, it would rise high above the city, giving guests a fantastic view.

The height of the balloon’s ascent was dependent on the price of the ticket. For one crown you could reach 350 feet, or three times the height of the Round Tower, and for five crowns as high as 1,000 feet. Some 305 metres in the air, that’s an incredible four times higher than Tivoli’s current tallest ride: the Star Flyer carousel swing ride.

19th century cloud coms

To make the ride even more exciting, one of the ropes that tethered the balloon to the ground contained a telephone cable. This let passengers make use of another novel invention from the time and make telephone calls from high in the sky so they could describe the fantastic experience.

Balloon Captain Johansen also enjoyed delighting visitors who wanted to keep their feet on the ground. In 1900, the adventurous and theatrical airman bought the restaurant Grøften and made it the talk of the town. Today if you visit Grøften, you can still see its ballooning history in the form of lamps shaped as hot air balloons.

Travel the world at Tivoli

The turn of the last century was also the heyday of ethnographic exhibitions drawing attention to life in different parts of the world. In 1905 Tivoli held its great colonial exhibition displaying artefacts, houses and people from its colonies: the Danish West Indies, Greenland, Iceland and the Faroe islands.

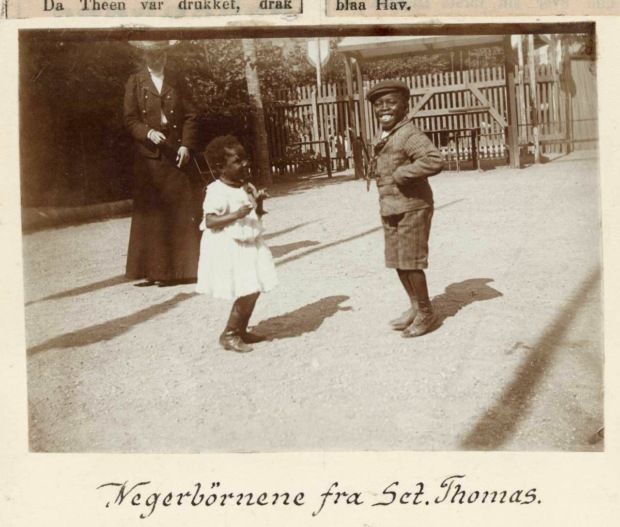

Each colony had its own pavilion complete with human representatives who wore clothes from their culture, showed off their local handicrafts and acted as guides. The West Indian pavilion had a traditional palm tree hut complete with coconut trees, animals and three people from the West Indies: William Smith and two children Victor Cornelins and Alberta Viola Roberts. The families of the two children had agreed to their trip to Copenhagen in return for the children receiving an education.

See the spitting child

At the time of the exhibition, Victor was seven and Alberta was four. Then as now, Tivoli was a paradise for children with lots to see and do. Victor was particularly fascinated by the Greenlandic Pavilion. In fact, he spent so much time running off to be with the Greenlanders that the two children were put in a cage to keep them in the Danish West Indies pavilion. Understandably, Victor was not happy at his loss of freedom and would show his displeasure by spitting through the cage bars at passers-by.

Crown Princess Louise was patron of the exhibition, and it drew a large crowd of over 100,000 people, including many government ministers and members of royalty.

Although hugely popular, the exhibition was beset with problems. In particular, the Icelanders protested loudly as they considered themselves superior to the other groups and didn’t want their pavilion to show their country as a primitive culture. To smooth out these concerns, Denmark agreed to show items and exhibits from its own agricultural history.

End of an era

The Icelanders’ protest was a sign of the changing times and Denmark’s numbered days as a colonial power. Just over a decade later, in 1917, the islands in the Danish West Indies were sold to the US and then, a year later, Iceland became an independent state.

And what happened to Victor and Alberta following the exhibition? Sadly, Alberta died in her teens but Victor completed his schooling and teacher training. He ended up as a highly respected deputy headmaster of a school in Nakskov where he lived until his death in 1985.