Things to do

Art Review: Modernism and the seductive lure of the machine

This article is more than 4 years old.

★★★★☆☆

Artist Maiken Bent is responsible for the layout of the exhibition (photo: Malle Madsen)

The current exhibition at Gammel Holtegaard focuses on three artists, all part of the avant garde, who were fascinated by mechanical things in all of their manifestations.

In the 1920s, Paris was the place to be for up-and-coming young artists. Bursting with creativity, The ‘City of Lights’ shone brighter than ever, attracting people from all over the world.

One of the prime movers in avant garde art, Fernand Léger, had recently set up his Académie Moderne, and Danish artist Franciska Clausen became one of his pupils, as well as his lover for a time.

Gösta Adrian-Nilsson from Sweden (known by his artistic name GAN) also met, worked with and was inspired by Léger and had a studio nearby.

Hi-tech admiration

Since the beginning of the 20th century, modern artists had become increasingly fascinated by machinery, mass consumption and images of consumer goods. Technology was not only a marvel in itself, as it also provided a rich imagery of wheels, screws, ropes, steam, chains and movement.

It might be thought that this enthusiasm would have waned somewhat when the exhibited artists were exploring this field, as the First World War had only just ended – with its highly mechanised slaughter responsible for at least 9 million military deaths and around 20 million severely wounded or crippled. Léger had even witnessed this at first-hand in the French Army.

But the 1920s were also about reconstruction, progress, putting the recent past behind – and just revelling in the joy of living.

The roar of the 20s

Clausen’s work from this period contains many references to machinery in the dynamic use of colour, form and rhythm, while GAN was fascinated by speed and the way people lived in the modern city.

The exhibition is shown in six rooms, each with its own theme, starting with ‘The Rhythm of the City’. In GAN’s picture from 1918 of a military parade, ‘Vaktparaden’ (parade of guards), you can almost hear the trample of horses’ hooves and the military band playing as it moves through the throng of spectators.

In the same room, Clausen’s ‘From Rue Delambre’ (1925) is a perfect example of how to simplify architecture down to the bare essentials of squares and oblong blocks of colour.

In 1923-24, Léger and American director Dudley Murphy, with input from Man Ray, made a film entitled ‘Le Ballet Mécanique’ celebrating the machine and the city through bursts of disparate images and objects that rush past with all the energy of a modern city.

Similar themes were later to be explored by Fritz Lang, Dziga Vertov in ‘Man With A Movie Camera’ and ‘city’ films such as ‘Berlin – Symphony Of A Great City’ by Walter Ruttmann.

Screws, wheels and machines

In ‘Køkkenstilleben’ (kitchen still-life) (1924), Clausen transforms objects from everyday life – such as saucepans, coffee machines and kitchen utensils – into geometric shapes, using them as a jumping-off point to investigate form and colour.

In an essay from 1949, Léger writes “to me the human body is no more important than keys or bicycles … they are the valuable plastic objects I can use as it suits me”. Clausen’s ‘Skruen’ (the screw) from 1926 places the spiral right in the centre of the picture like a figure in a portrait, as if to anticipate Léger’s statement.

The turn of the screw (Museum Salling Kunst)

Another work by Clausen, ‘Studie til Karaflen’ (Study for the carafe) (1927), explores the play of reflections on the surface of a humble carafe. This mundane object has been transformed into a series of geometric shapes, but still remains recognisable for what it is.

Not alone

These artists did not just exist in a vacuum, and the influences of other artists and schools are plainly visible in some of their works.

GAN was obviously inspired by German artists from Der Blaue Reiter school, such as Franz Marc and Kandinsky. His treatment of the horses in ‘Cowboy och häster’ (cowboy and horses) (1918) is clearly a nod to Marc.

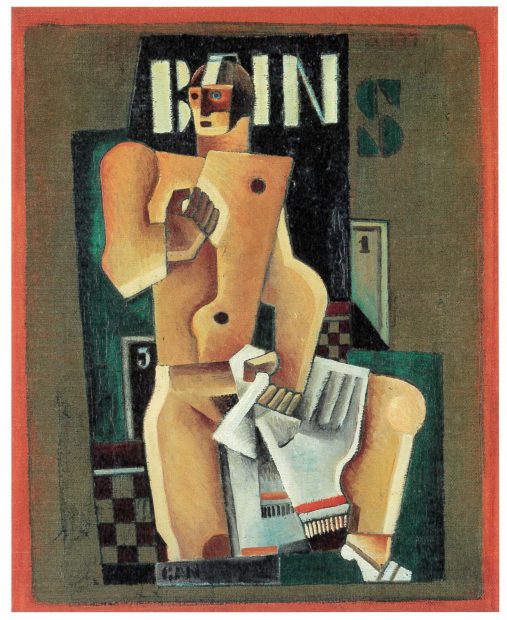

His human figures are also reduced to geometric shapes and blocks of colour: for example the man shown taking a bath in ‘Bains’ (baths) (1923) and the matador being trampled by the bull in ‘Tjurfäkting’ (bullfighting) (1933).

Taking an early bath (Canica Kunstsamling, Oslo)

Into the world of dreams

The exhibition then takes a turn away from the machinery of the title and enters the world of surrealism. Here, the sub-conscious and the dream world takes over. GAN’s works in particular show similarities with the work of Dali.

The final section is really a pointer to the future, as these artists began to grow in different directions, and their work is increasingly divergent from that of their mentor Léger. Clausen, who in in 1929 was a co-founder of the group of artists called Cercle et Carré (circles and squares), leans towards pure geometric abstraction and non-figurative painting. This also includes other modernists such as Mondrian and Robert and Sonia Delaunay.

GAN’s work also becomes more abstract, as can be seen in the picture ‘Plangeometrisk målning’ (plangeometric painting) from around 1930.

To sum up, although this exhibition doesn’t quite seem to ‘do what it says on the tin’, it hardly matters, as it is a fascinating look at an exciting and dynamic period of modern art. The work of GAN in particular was new to me and I was very happy to make his acquaintance.