Business & Education

Brown hygge: Recalling how even in 1978, Denmark was behind the curve

This article is more than 4 years old.

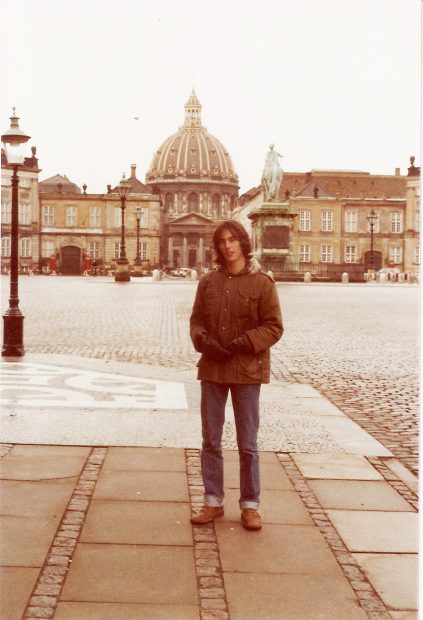

Everything had a mahogany hue: from the wallpaper and floor matting to the wooden panelling in the bars. But fortunately the intrepid hero of this tale had a brown jacket á la Elvis Costello, adorned with badges up the lapels

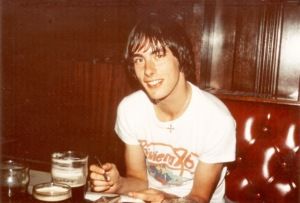

Englishness was so exotic back then that Stephen was often asked for autographs in pubs

Seen from a distance of 40 or more years, the Denmark in which I landed in the summer of 1978 seems a very different place from the Denmark of today.

As my daughter perceptively pointed out whilst chuckling over some photos of the youthful me, everything seemed brown. People had hessian wallpaper and coconut matting on the floors. The local bars all had brown wood panelling, usually seen through dense clouds of tobacco smoke.

I arrived here as a callow youth of 21 in search of adventure and following love. A year or so before I’d met a Danish girl working in England during her summer vacation and we’d kept in touch. I initially moved in with her and her parents in the leafy suburb of Sorgenfri and all seemed set fair – at least to start with.

Brown hygge culture shock

On the streets I noticed most people were white and still had long hair. There was an abundance of washed denim and even the odd pair of flared trousers. All in all, it felt a bit like stepping back in time. Back then I had a pretty radical short haircut and sported a brown suit jacket from an Oxfam shop á la Elvis Costello, with badges up the lapels.

As an EU citizen I was entitled to remain in Denmark for up to three months as a tourist, but after that I’d need a residence permit and identity number (CPR number). In those days, this was obtainable from the immigration police.

However, in order to get a residence permit you had to have a job lined up. In a catch-22-like twist, in order to get a job you needed a residence permit.

Together with my girlfriend, who came along to provide much-needed moral support and possible interpreting services, we rolled up at the local labour exchange. The bored-looking middle-aged man behind the counter didn’t seem overly impressed with my resume, and I must admit that I couldn’t blame him. My experience of ‘real’ work was minimal: I’d had paper rounds, delivered groceries and worked Saturdays in a shoe shop.

In order to build up a ‘war chest’ for my Danish trip, I’d been temping during my summer holidays for the Manpower agency. My jobs included working in a petrol station on the other side of the fence from one of the main runways at Heathrow (great view of Concorde taking off!), and as a warehouse employee for an industrial air filters firm.

Gråbrødretorv grudgingly

After casting a glance at this, the man asked me whether I spoke Danish. When I answered in the negative, he basically told me the best thing I could do was to go back to England, as I’d never be able to get a job in Denmark.

I was somewhat crestfallen, but my girlfriend pointed out that according to the law he was obliged to offer me something. Grudgingly, I was given a choice between a dishwashing job in a restaurant or a cleaning job. I chose the former and was sent along to Bøf & Øst, a restaurant on Gråbrødretorv that is still there today, for an interview.

They were not exactly ecstatic to see me either. Once again all my girlfriend’s powers of persuasion were needed to get them to take me on. Luckily she succeeded and I was able to start more or less straightaway, working a shift from lunchtime to around 11:30 at night.

In need of bannisters

It was pretty lonely to start with as my co-workers were Turks and Yugoslavs – the ‘guest workers’ of the day – and they didn’t speak English, only their own languages and Danish. The work was quite hard and the restaurant shared its dishwashing facilities with the restaurant next door. As it was an old building, there were some pretty narrow, winding staircases to negotiate whilst carrying heavy trays of glasses or plates from one place to another.

Another problem was that I was still living in the suburbs and the last S train from Nørreport left at about midnight. We often worked late, and many’s the time I had to do a four-minute mile to reach the station in time.

Stinky grease punkie

Added to that, my hair and clothes always smelt strongly of frying fat. I also noticed that the detergent from the dishwashing process softened the rubber soles of my shoes, so there was a real danger of them literally sticking to the carpet when entering a house.

On the other hand I was earning money and was able to get the coveted residence permit. I also managed to strike up a conversation with some of the waitresses. They seemed pretty stand-offish at first, but later one of them explained the turnover amongst the dishwashing contingent was so high it hardly paid for the girls to remember their names.

After about six weeks I felt like a veteran. I’d also decided I’d really like something else! As luck would have it, my girlfriend had a clerical job for a company making chemicals and fertilisers. She was about to return to her studies and managed to get them to take me on for half a day.

This was the pre-computer era and the work consisted largely of alphabetising and filing letters and coloured copies of letters. To supplement this I had a cleaning job in a nearby school which was not too arduous, so it definitely felt like a step-up.

Upping anchor

Just before landing these jobs, I’d applied for a post in an international shipping organisation based in Østerbro. They wanted a native English speaker to work in their basement print shop and to help out in the membership department. I’d gone to an interview, but had heard nothing. In retrospect it may not have helped that I’d turned up in my jacket with the badges.

On the other hand, I felt the interview had gone well. I’d been told it wasn’t a problem that I’d no experience of printing – I could learn on the job. But as a parting shot the interviewer asked me whether I was opposed to capitalism, and that was rather a humdinger! I waffled my way out with some trite phrases about good and bad points with all economic systems and thought I’d got away with it. (Mind you, if anyone asked me that question today, I’d have to admit that I’m much more ambivalent now than I was then!)

To cut a long story short I was later offered the job (the other applicants were even worse!) and stayed there 36 years. I ended up as editor of the organisation’s membership magazine and paper publications, having learnt how to deal with journalists and printers and lay out a magazine electronically.

I’m also still happily married to the girl who lured me over here in the first place. A pretty good result really, although I say so myself!