Business & Education

Unusual and unexpected coalitions, and distinguished and dastardly PMs

This article is more than 6 years old.

From assassinations attempts to Anker’s acquiescence to Anders Fogh’s assertiveness

With the 2019 General Election coming up on June 5, it would be churlish not to recall some of the most memorable contests, leaderships and coalitions in Danish history.

After all, for many of us internationals, Danish politics couldn’t be more different from the two-horse races in our own countries. Next Wednesday, no less than 13 parties will be vying for the people’s votes. There is never an absolute winner.

Instead, the biggest parties in the red or blue bloc, which are expected to be Socialdemokratiet and Venstre, will try to persuade the queen they are capable of forming a coalition. On some occasions, those hopes have been completely dashed!

It harks back to a time when the monarch not only had the final say, but pretty much decided everything. So in the immortal words of Maria von Trapp, “Let’s start at the very beginning.”

935-1849: Ironies of absolutism

The monarchy was formed in 935, but it was not initially absolute like most other European crowns, although few kings are remembered for abusing their authority in the vein of somebody like Ivan the Terrible or Henry VIII, for example. As an elective monarchy, the next king was always chosen, even if it almost always was the eldest son of the king!

This continued until the reign of Frederik III, and perhaps it was his insistence in the 1660s on the monarchy becoming absolute, thus securing the crown for his son, which unnerved the status quo, as it wasn’t long until the positions of storkansler (grand chancellor – 1699-1730) and statsminister (minister of state – 1730-1848) emerged – forerunners of the position of PM.

One of the first ministers of state wasn’t even born in Denmark. While Britain had the Pitts, and the US the Adams, Denmark’s first political dynasty was the Bernstorffs, and it all began in 1751 with the appointment of Count Johann von Bernstorff to the privy council. As statsminister, Bernstorff is credited with maintaining neutrality throughout the Seven Years’ War, and two of his descendants – his nephew and grand-nephew – went on to take the post.

The most famous statsminister of them all was also German-born. When Johann Struensee was appointed physician to King Christian VII, few imagined he would make his way into the royal family – quite literally. A radical thinker and star of the enlightenment, Struensee banned the slave trade and censorship of the press.

Nevertheless, he is best remembered for his affair with Queen Caroline Mathilde and their ‘love child’, Princess Louise Augusta. He was executed shortly after the affair was exposed.

1849-1953: Chamber pot system

When the country adopted a constitution in 1849 under Frederik VII, the way was clear for the country’s first prime minister, and that honour fell to Adam Wilhelm Moltke. His appointment coincided with the foundation of the Danish Parliament (Folketing), which began life as the lower chamber of the Rigsdag, although it held equal power with the landed gentry’s chamber, the Landsting.

he bicameral system would stay in place for 104 years, before the Landsting was abolished in 1953, leaving the Folketing to operate as a unicameral legislature.

During that period, there were many PMs who made their mark – most notoriously of all Ditlev Monrad, who presided (indecisively according to Christian XI) over the debacle of 1864, Denmark’s darkest hour. Just months after losing the Second Schleswig War and the vast territories of Schleswig and Holstein with it, Monrad legged it to New Zealand!

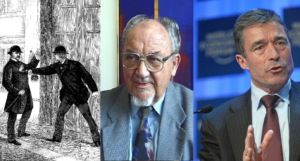

The events of 1864 left the country in ruins, and frugally-minded Jacob Estrup was just the man to get them out of trouble. As PM for 19 years, he presided over a period of austerity from 1875 to 1895, and in 1884 (with the backing of the Landsting) stubbornly refused to resign, even though his Højre party had only won 19 out of 102 seats in the election. Even an assassin’s bullet in 1885 couldn’t get rid of him a year later, making him the only Danish leader to ever be shot at.

Julius Rasmussen opened fire at point blank range, contriving to miss with the first and hit one of his coat buttons with the second.

1973-2015: Rise of the kingmakers

The 1973 election is considered the birth of modern politics in Denmark. In 1971 only five parties won seats, but this rose to an unprecedented 10 in 1973 thanks to an 88.7 percent voter turnout (the highest since 1920), with two newly-established parties winning 42 seats in a contest that quickly took on the name ‘The Landslide Election’. Venstre formed the smallest minority government in Danish history with a mere 22 seats and Poul Hartling as PM. Despite claiming 46 seats, Socialdemokratiet and its leader Anker Jørgensen could only watch from the sidelines, although less than two years later he reclaimed the position of PM.

History then repeated itself in 1990 when Socialdemokratiet once again won the most seats but was unable to form a government with its leader Svend Auken as PM due to the refusal of Radikale to support him. It might sound bizarre to some, as Radikale won only seven seats to Socialdemokratiet’s 69, but their refusal to back Auken enabled Konservative leader Poul Schlüter, with just 30 seats, to remain in power with the help of Venstre (29 seats).

The next two elections in 1994 and 1998 saw cross-spectrum coalitions led by Poul Nyrup Rasmussen, with Radikale in its customary role as kingmaker, take control.

The red bloc vs blue bloc divide, which we today take for granted, made its return in 2001 when Anders Fogh Rasmussen became the first Venstre leader in 26 years to become PM. The victory finally broke a several decades long pattern that had seen Radikale decisively determine who would rule. Dansk Folkeparti’s emergence in 1998 played a significant role, and immigration in 2001 proved to be the key issue as Venstre (56), DF (22) and Konservative (16) formed a strong right-wing coalition. With Radikale not tipping the scales, the right-wingers no longer needed to collaborate across the political centre, and the VKO alliance lasted for ten years.

Back in 1998, few would have ever envisaged DF being strong enough to form its own government 17 years later, but 37 seats in 2015 put them in that exact position. Socialdemokratiet (47) won the most seats, but saw support for its government partners SF and Radikale crumble as they lost nine seats each. The blue bloc’s majority put Venstre (35) in the driving seat, and after lengthy negotiations it formed yet another minority government.