Things to do

Performance Review: Daring to ask whether humanity’s number is up

This article is more than 7 years old.

★★★★☆☆

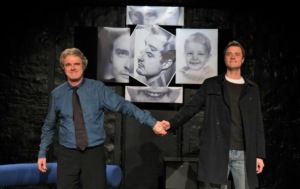

Ian Burns and Rasmus Emil Mortensen take some well-deserved applause (photo: Hasse Ferrold)

The evening began with a scientific and spiritual debate between a panel of three experts on various matters related to the subject of human cloning. This managed to set an appropriate tone of unease by asking the many ethical questions surrounding human cloning.

Setting the stage

It’s a practice for which there is, technically, every possibility and only varying degrees of limitations put in place – depending on where you live.

While the UK and Denmark allow the cloning of human organs, solely in the interest of curing diseases, countries like the USA have next to no limitations on the practice – particularly for privately-owned companies.

Inevitably the evening’s focus turns to the realms of macabre science fiction with the idea that we may one day attempt to resurrect lost loved ones by means of cloning – thus setting the stage for the evening’s main attraction, Caryl Churchill’s play ‘A Number’.

Solid performances

Essentially a series of meetings between one man, Salter, and his ‘sons’ – the play explores relatable, universal notions of uniqueness and themes of nature vs nurture, sibling rivalry and familial favouritism.

The widowed Salter, solidly portrayed by That Theatre’s co-founder and artistic director Ian Burns, is a complicated, selfish and searching man. One by one we encounter his sons – only one of whom is not a clone – and all of whom are played with great relish by Rasmus Emil Mortensen (who previously excelled in That Theatre’s Marathon).

With each meeting we bear witness to a new variation on not only the son but, to a subtler degree, also the father. Burns imbues Salter with all the brazen bluster of a father who in one scene brushes off any mention of his past with ease, and in the next is a broken mast of a man no longer sure of where to set sail. Ultimately he ends up in the US, talking to a new ‘son’ for the first time.

Poirot becomes philosophical

Churchill’s dialogue is well served by Mortensen and Burns who make admirable efforts to naturalise the text with stumbles and overlaps, all of which goes some way to drawing attention from the expositional work being done in the subtext.

There we get snippets of the background story – Salter’s wife’s death and the unauthorised use of his son’s DNA by the cloning company – but much of this comes courtesy of Salter who quickly reveals himself to be not only be an alcoholic but an untrustworthy source of information.

Churchill casts us as detectives, leaving us to do the narrative work, but after that investment we’re rewarded with a conclusion that is less a narrative one and more philosophical in nature. An abrupt end leaves one with the impression of the substance being, at least initially, slight. However, in hindsight, the final note is a profound one.

Similarities to Solaris

Churchill’s closing point echoes Stanislav Lem’s observations from his master work Solaris: that wherever man goes, even when traversing to the furthest reaches of the universe, he is looking for himself. For this reason alone, what he finds will often be interpreted as himself, wrongly or not. Otherwise, death, fear or boredom awaits.

When Salter meets the most settled of the clones – a reasonably successful, contented, well-balanced, unassuming young American – his disappointment is palpable. This clone is uninteresting to him, because this young man is untroubled, uncomplicated – and Salter sees NOTHING of himself.

This posits interesting questions about the degree to which we impress ourselves, our values and our personalities on our children. In this sense, to what degree do all parents ‘clone’ themselves via their children? And at what point does this narcissism become dangerous?

A slight criticism

Visiting Brit Helen Parry has lent her muscular directorial hand in shaping this tight but minimal ship – her focus obviously being very much on performance.

Whilst serving the production well, it apparently comes at the expense of other considerations: the lack of any frills in say, the art department, combined with the play’s short running time (particularly without the 45–minute debate, which was a premiere-only event), which could leave the audiences with the impression of a distinctly ‘slight’ evening.

Nevertheless, the opportunity to see this thought-provoking play performed by two gifted actors should not be passed up.