Business & Education

Kids not the only ones up to mischief at Fastelavn in years gone by

This article is more than 7 years old.

Ahead of the feastday tomorrow, we recall how whole communities enjoyed a day of high jinks to celebrate the end of winter ahead of the onset of a lean Lent

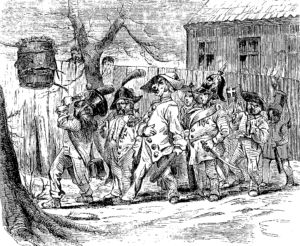

Bashing the barrel (photo: Illustreret Tidende)

Terrible stories circulate around the traditions behind Fastelavn, the beginning of the carnival season. Some claim it began as a pagan holiday when the peasants celebrated fertility by getting dead drunk, wearing outlandish costumes, killing cats trapped inside barrels and ripping off the heads of live geese. And the only thing they agree about is that today fastelavnsboller are special treats filled with jam or cream and drizzled with melted sugar.

However, the true story of Fastelavn involves both the devil and the church, the farmhands and the priests, and shows that traditions were spread throughout Europe with their own regional variations. A cat was not always slaughtered in cold blood after being beaten out of a barrel for sport. Sometimes it was only chased out of town.

A last blow-out before Lent

Before the Reformation in Denmark in 1536, the country was a Catholic nation and celebrated Lent. Fastelavn was the last celebration before the 40 days of fasting. In old Danish this festival week was called fastelag, which meant ‘et muntert lag før fasten’ or ‘in good company before fasting’. The older word is still used in Swedish. Modern-day Fastelavn continues to fall between February 1 and March 7, depending on the religious calendar, which sets Easter Sunday based on the cycle of the moon and Fastelavn 40 days prior.

After the Reformation, the ruling Protestant priests were not thrilled with Fastelavn, which was essentially the adults’ time to run wild. By this time, however, the costumes and games had become a fixed tradition before Lent, even though the celebration pre-dated Christianity in Denmark. In pagan Denmark there had been a festival heralding the coming of spring and fertility, before the Catholics coupled it in with their own holidays. Afterwards Fastelavn became so well integrated, that Protestant priests and bishops had no way of preventing it. There were no longer any rituals about fertility, other than some extremely heavy drinking.

All about the procession

In the countryside, the most important part of Fastelavn was the procession, or parade, of townspeople going from farm to farm on horseback and by foot, enjoying the hospitality of all their neighbours. Unmarried men rode horses borrowed from local farmers, and unmarried women decorated the horses and put together masquerade outfits for the benefit of their favourite men.

Participating in Fastelavn was an important local event, because if the town disapproved of one of the farmers, the procession would not visit them.

Author Meir Goldschmidt was born in 1819 to a Jewish family in Copenhagen, and he described his family’s attempt to join Fastelavn after his father bought a farm in Valby. “Our gate stood open like all the others, but the procession did not come to us at all. We children felt the shame that fell over our farm, so deep that we stood and cried behind the gate posts, and just dared to look at the festival that seemed to be for all the others, only not for us.” It could take generations to learn the customs and fit into the society of a small town.

Let the games begin

Games were an integral part of the holiday, usually including athletics races and riding games. In Valby in the 1830s it was popular to play ‘stick the straw man’, in which riders with lances went around in a circle trying to stab a straw man and lift him up on the point of their lance. According to Goldschmidt, the straw man was “dressed up as a Turk in blue and white colours, with a red turban, gold brocade and glass beads”.

In Skåne and other parts of eastern Denmark, it was common to dress the straw man up as a Prussian. Many towns liked to change the games from year to year, sometimes challenging riders to collect rings or grab the neck of a goose, while it was hanging upside-down. The neck of the goose was coated in soap, and the rider had to rip the animal’s head off the body, so the event was both challenging and gruesome.

Beating the barrel

In the Middle Ages, cats were often killed as a representation of the devil at work or the cause of any number of misfortunes. Up until the early 1800s in Denmark, it was common to trap a black cat inside a barrel for Fastelavn, which was then hung up over a main street in town. The game was to beat the cat out of the barrel with wooden bats or sticks, either on foot or on horseback. When the barrel broke, the cat would fall out and be killed or chased out of town. There was also a great prize in some towns for the person who broke the barrel. He, or his father if the winner was a boy, would not have to pay taxes for the whole year. Later the cat was replaced by a cardboard cat or a doll.

This tradition has continued into the modern holiday, where children break a small barrel by taking turns with a wooden bat, but only confectionary and toys fall out. Another old game that lives on involves participants with their hands tied behind their backs trying to eat a Fastelavnsbolle or roll that is hung up by string at mouth level. This sounds easy, but the soft cream-filled buns are not tied up because they will not hold – only the firmer rolls can withstand this game.

Kids are in charge

Traditions and games at Fastelavn were also influenced by the Dutch, some of whom settled in Amager in 1521. King Christian II invited farmers from the Netherlands to settle in Denmark and show others how they could get the thin soil near the ocean to grow many kinds of vegetables. The project was a success and the town they settled in was known as Hollænderbyen. Today the same town, now called Store Magleby, hosts riding games, the breaking of the barrel and other traditional Fastelavn events in connection with Amager Museum.

Above all, the holiday today is one mainly celebrated by children. They beat the barrel during the day, and then in the evening they dress up in costumes, go door-to-door asking for confectionary or money, and eat sweet pastries – not dissimilar to what many children do on October 31. And sometimes, just like at Halloween, they even play tricks – like the ones referred to in a poem for Fastelavn, which became popular in the 1930s (see below) – so if you hear that knock on the door and the cupboard (or wallet) is bare, you might consider pretending you’re not in if you don’t want a nasty fright coming in through your letterbox.