News

Living the perfect American Dream – in Denmark

This article is more than 8 years old.

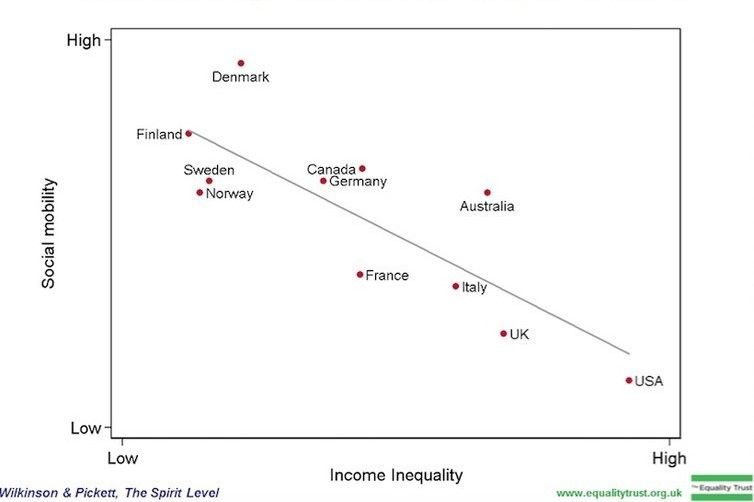

Research shows that Denmark has the highest social mobility because of high income equality

The flag of the new American Dream?

Owing to the ubiquitous rags-to-riches story told by Horatio Alger in the 19th century, the idea of living the perfect ‘American Dream’ has almost become a universal phenomenon.

Research, however, shows that far from being the land of opportunity, the US has very low social mobility. So in fact, you are much more likely to achieve the American Dream if you live in Denmark.

Social mobility lower in unequal countries

In their book called ‘The Spirit Level’, professors Kate Pickett and Richard Wilkinson from the University of York demonstrated a clear research-based link between high levels of income inequality and low levels of social mobility.

Social mobility is the ability of individuals, families or groups to move up or down the social ladder in a society, such as moving from low-income to middle-class.

The book talks about the pernicious effects that inequality has on societies: “eroding trust, increasing anxiety and illness, (and) encouraging excessive consumption”.

It shows that for each of eleven different health and social problems including physical health, mental health, drug abuse, education, imprisonment, obesity, social mobility, trust and community life, violence, teenage pregnancies, and child well-being, outcomes are significantly worse in more unequal rich countries, such as the US.

READ MORE: American candidates queued up for Danish jobs

Denmark hailed as an exemplar

Although not completely immune, Denmark has less of a problem related to social mobility compared to other wealthy countries.

In 2015, an OECD study showed that income inequality reached historic highs. This was due to the fact that in most of the OECD countries, the income gap was at its highest level in three decades, with the richest 10 percent of the population earning 9.6 times the income of the poorest 10 percent. That ratio was at seven to one in the 1980s.

In Denmark, on the other hand, the richest 10 percent earn 5.2 times more than the poorest 10 percent, the lowest ratio among all OECD nations.

Although some researchers have refuted the findings, the Scandinavian model of social welfare is still considered exemplary by policy analysts across the world.

The situation in the US and Britain

Contrary to Denmark, a study published in the US last year used earnings data of Americans to measure how fluidly they move up and down the income ladder over the course of their careers.

The paper concluded that irrespective of one’s educational background, there has been a significant decline in upward mobility among middle-class workers since the early 1980s and the increasing income inequality is one of the contributing factors.

With statistics continuously skewing towards the negative, the opportunity to live the ‘American Dream’ is much less widely shared today than in the past. Attitudes about inequality have also altered over the years.

READ MORE: Denmark eyeing longer tax breaks for highly-skilled foreigners

In 2001, research found that the only Americans who reported lower levels of happiness amid greater inequality were left-leaning rich people – with the poor seeing inequality as a sign of future opportunity.

Such optimism has since been substantially tempered: in 2016, only 38% of Americans thought their children would be better off than they are.

Similarly, a study conducted by the British government’s Social Mobility Commission in June 2017 showed that policies related to social mobility have failed to significantly reduce inequality between rich and poor despite two decades of interventions by successive governments.

The report suggested some improvements that included cross departmental government strategy, ten-year targets for long term change, and a social mobility ‘test’ for all new relevant public policy.

READ MORE: A record number of foreign workers in Denmark

It was also recommended that public spending be redistributed to address geographical, wealth and generational inequalities.

Moreover, it advised that government coalitions with local councils, communities and employers create a national effort to improve social mobility.

So far as they go, applying these lessons could indeed be helpful. But specific policy recommendations to address social mobility will not reduce the income and wealth inequalities which are at its root, Pickett and Wilkinson wrote.