News

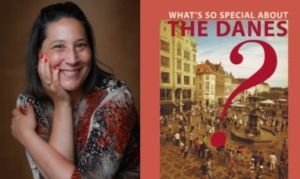

Book Review of ‘What’s so Special about the Danes’

This article is more than 8 years old.

★★★★

It’s a recommended read providing you’re well accustomed to Denmark

Stephanie Madsen’s ‘What’s so Special about the Danes’ is an antithesis to the legion of books released in recent years that attempt to explain how various Danish elements – such as hygge, happiness, television shows like Borgen and Forbryldsen, and New Nordic cuisine – have made such a big impression worldwide.

A Brit-free zone

Central to this explosion in the popularity of Faroese knitwear have been the British Danophiles – the Guardian-reading viewers of BBC 4 who the likes of journalists Michael Booth (The Almost Nearly Perfect People) and Helen Russell (The Year of Living Danishly) have been quick to capitalise on.

In contrast, Madsen’s book couldn’t be more non-journalistic, and she hasn’t interviewed or consulted a single Brit. Instead, most of the interviews are with people from France – she was born in Paris and raised in Haiti – Denmark and the US, the two countries she has primarily lived in as an adult.

Forthright opinions

The absence of whinging, faintly funny Brits might be welcome news to many, as is the book’s brevity, easy-to-read nature and overall plain talking. Madsen doesn’t hold back or gingerly speculate like she’s afraid the Danish people will launch a collective lawsuit.

She offers forthright opinions on why the Danish are the way they are, and within her well-thought out theories are insights that many international residents will appreciate, although they might be less accessible to new arrivals or non-residents who often need to be spoon-fed the basics.

So while this book’s haphazard narrative might bewilder the recent wave of journalistic books championed by the likes of Jon Ronson – many will enjoy it, because didn’t you know: the people have had enough of experts!

Not one for the purists

From a journalistic perspective, there are plenty of flaws, particularly with the interviews, which are mostly a random procession of expats and repats repeating old hat, with the occasional nugget hidden here and there.

Most of them read like they’ve been transcribed by a sixth-grader. If the intention was a Godfather-style staccato prose (“I believe in America. America has made my fortune” etc), it starts to grate pretty quickly.

Others are long chunks of text that were most probably written in an email to Madsen, which she just copied and pasted and then crossed off another two pages of her book.

There’s a good interview of Martin Lidegaard, a former foreign minister, but a risible one of Bertel Haarder, one of Denmark’s most distinguished politicians, which pretty much ends before it gets started, suggesting he gave her short shrift when she asked him about a priest who doesn’t believe in God.

Its inclusion is pointless. The only reasonably explanation is that he’s a big name, and Madsen hopes the readers won’t notice he only said two words and that they both began with ‘N’.

Another criticism would be that at times it’s hard to know whose opinion is being presented: Madsen’s or the subject’s.

Educational, enlightening, easygoing

Nevertheless, the book is an easy read. Despite Madsen not being a native English speaker, there are no language issues: it’s well edited and the sentences are never overly long. Madsen’s chosen to play it safe and not be too ambitious with her prose, and accordingly there’s very little wit.

Aside from a few misrepresentations (including a claim that Denmark is number one for the consumption of happy pills – not true we’re afraid), it’s generally well researched.

Most appreciated were the insights regarding Denmark’s Protestant roots, small size and identity, climate and employment record. They alone were worth the effort of what amounted to only two to three hours of reading.

I would have personally preferred to read more about the authority-challenging year of 1968 and its effects on Danish education and society over the next decade than lengthy concerns expressed about gender equality on company boards – a passion project, it would appear. A few more insights about what the future might hold in store for Denmark wouldn’t have gone amiss either.

Overall I felt educated, enlightened and at ease reading this book and would recommend this to ‘lifers’ interested in some intelligent observation about the nation whose country they call home.

Purchase a copy here.