Business & Education

Remembering Tivoli’s founder: a showman with a fondness for champagne and jazzy waistcoats

This article is more than 8 years old.

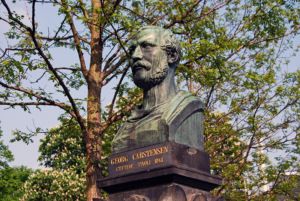

Georg Carstensen Plads honours a favourite son of Frederiksberg whose gift to Copenhagen remains its most cherished possession

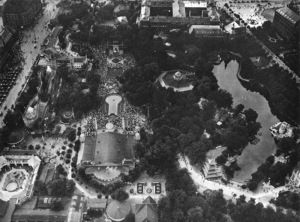

This 1922 photo clearly shows the moat turned boating lake (photo: Eduard Spelterini)

Sometimes you have to trust the visionaries. Like Kevin Costner’s character in ‘Field of Dreams’. “If you build it, they will come,” is the kind of business plan that would get most people locked up, but come they did.

And similarly there were a few raised eyebrows when Georg Carstensen, the founder of the Tivoli Gardens in 1843, said the themepark would “never finish growing” – hardly the thing you want to read in an investors’ prospectus about a construction project.

So given that modern urban squares tend to have that unfinished look about them – paths with no purpose, benches without backs, a conceptual art statue that looks like a children’s playground ride with a missing swing – maybe it was apt naming one after Carstensen.

Square’s inauguration

On Thursday May 18, the mayor of Frederiksberg, Tivoli’s chief executive Lars Liebst and other dignitaries gathered for the inauguration of Georg Carstensens Plads.

Among those present were (right-left) Tivoli chief executive Lars Liebst, Frederiksberg mayor Jørgen Glenthøj and descendant Edward Carstensen, whose grandfather was the brother of the founder. “It feels very big that Georg Carstensen now has his own place in Frederiksberg,” he said. “It is a huge recognition of his significance for the city and Denmark. It’s something we’ve dreamed of in the family for generations and now it’s coming true. It feels right.” (photo: Hasse Ferrold)

The urban square, located just west of Frederiksberg Town Hall Square, becomes one of several place-names that recalls the contribution of one of the wealthy municipality’s favourite sons.

Nearby Amicisvej is named after Gaëtano Amici, the esteemed Italian firework manufacturer who was invited by Carstensen to supply the pyrotechnics to the early days of Tivoli, while Alhambravej is name after an amusement park founded by Carstensen in Frederiksberg, which opened eight months after his death in 1857.

A city centre oasis

Next year will mark 175 years since Carstensen was given the right to found the world-famous Tivoli on a barren patch of land outside the city walls.

Carstensen was one of the first of a string of entrepreneurs to realise the potential business opportunities provided by the newly-opened railway station. He spent his early life in Algeria and later witnessed the foundation of pleasure gardens in other European capitals such as London, Paris and Vienna, becoming convinced the same could be achieved in his own capital city.

Carstensen’s proposal was to build an extensive pleasure park, designed with the aim of allowing city dwellers to escape the “violence and boisterousness of the town and relax in a sea of tranquility”.

In need of pleasure

Copenhagen was a walled fortress-like city at the time, and the terrain outside the city bastion was laid bare, fulfilling the role of a demarcation line. Built beside the city’s watery fortifications, the moat was transformed into Tivoli’s boating lake. These were violent times, and in order to enter or leave the inner fortress, city-dwellers had to pass through one of the ‘posts’ – gates that surrounded the city.

Many citizens lived in abject poverty without running water or toilets. Entire families shared a single room in working-class districts such as Vesterbro and Nørrebro outside the city walls. At the same time, however, wealth was abundant due to Copenhagen’s success as a busy trading port, which provided a gateway for ships travelling through the Baltic and beyond.

Bequeathed by the king

The site of the proposed pleasure gardens was just outside Vesterport – today just the name of a railway station, but back then very much the ‘Western Gate’.

Although some city councillors were unsure of Carstensen’s idea, the newly-crowned Christian VIII saw the pleasure gardens as a perfect opportunity to deflect the public’s attention from the country’s political and social problems. He quickly granted Carstensen the right to build on 59,100 sqm of land, which lay just outside the city’s defensive fortifications.

Not having great personal wealth, Carstensen had to enter into delicate negotiations with businessmen and financiers before work could get underway. However, once the necessary financing had been agreed, construction was soon on track.

Work was progressing smoothly until a gruesome find caused workers to down tools. Labourers were horrified to come across well-preserved human remains buried under the soil, with some refusing to continue their grisly task. It turned out that the Tivoli site had been the scene of bloody battles against both British and Swedish invaders.

Champagne Carstensen

Tivoli first opened its doors to the public on 14 August 1843. Carstensen, always the showman, was at hand to shake the hand of every one of the 3,615 visitors who passed through the gates on that very first day.

The attraction included stalls, live music, merry-go-rounds and a working theatre, but what really caught the public’s imagination was the futuristic light show. Although pretty tame by today’s standards, the sight of gas-lighting illuminating the entire gardens was a sight to behold that took most visitors’ breath away.

The gardens were a success, and Carstensen used the profits to finance other business ventures including journals and magazines, becoming in the process one of the country’s first press barons.

Rumours of his lavish lifestyle abounded in those first heady days of success. It was said that the Tivoli designer owned over 100 waistcoats and never drank more than one glass of champagne from the same bottle.

The good life continued for the next six years, until disagreements with financiers led to the famed businessman quitting Denmark – and his beloved Tivoli Gardens. Copenhagen had lost one of its most colourful characters.

Disappointment abroad

Carstensen’s exile, however, was not a happy one. His first wife died in the Danish West Indies (later the US Virgin Islands), and a business venture in New York collapsed.

When the Tivoli founder arrived back in Denmark in 1855, the lavish lifestyle was over. The story goes that the designer and builder of Tivoli was forced to pay the full admission fee to enter his most famous creation just days after his return.

However, Carstensen still found time to plan one of Copenhagen’s first tram lines. He applied in early 1856 for permission to construct and operate a tram line between Frederiksberg Runddel and Tivoli, but died before his plans could be realised.

Ensured of his legacy

But there would be no destroying his legacy – not even the Nazis could manage that. During the Second World War, they blew up part of the gardens as a reprisal for acts carried out by the Danish Resistance.

By then, Tivoli had become the capital’s most popular tourist attractions, drawing in visitors from all over Europe and beyond. It offered not only pleasure but romance, as it is often said that countless love affairs have sprung up under its numerous trees.

And Carstensen’s words continue to echo through their branches. He once said that “Tivoli will never finish growing” and it is a mindset and philosophy central to the ethos of Tivoli that still prevails today.

Since its opening 174 years ago, the park has grown to fully 82,717 sqm in size, and barely a year passes without a new addition.