Business & Education

On display, then bottoms away at the academy

This article is more than 8 years old.

How a group of artists stood up to the stale sensibilities in the name of free art

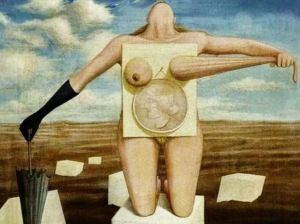

Genius or smut? (photo: Wilhelm Freddie)

When the avant- garde art group Grønningen launched an exhibition at the Art Academy’s Charlottenburg venue overlooking Nyhavn in Copenhagen in January 1933, offending the public’s sensibilities was possibly the last thing this innovative band of artists had in mind.

They hired theatrical decorator Svend Johansen (1890-1970) to design and paint the exhibition poster.

Known for his provocative sense of humour, Johansen decided to shake up both the art world and the public by choosing a highly questionable motif for his poster: a voluptuous woman with a bare behind.

While such an image may seem rather innocent to us today, the year 1933 was part of an altogether more modest era. To say the poster raised a few eyebrows would be an understatement. The public was more or less used to new and innovative movements in the sometimes confusing world of art, but this was more movement than most could bear.

Public outraged

The poster was deemed “a horrifying sign of the times”, and the well-rounded maiden depicted therein characterised as “of obvious easy virtue”, and a “Jezebel … enticing us into the exhibition with unspoken promise of forbidden fruit in her provocative gaze” by disgusted citizens writing to the newspapers of the day.

Public outrage at the poster was perhaps best illustrated when members of the royal family paid an official visit to the exhibition. Responding to popular demand the police stepped in and ordered the poster’s most conspicuous element to be covered up.

Exhibition organisers were forced to capitulate. Artists Albert Naur and Hans Bendix masked out the offending posterior by pasting an advert for Jean Gaugin’s ceramics on top. Although the delicate sensibilities of many art lovers of the day were thus accommodated, the poster’s new ‘clean’ image became a source of much hilarity.

Johansen claimed to be perplexed by the reaction to the provocative buttocks. He argued that such a “motif”, as he called it, had been used in art for centuries.

A fresh coat

In fact from the 1890s onwards, the nation’s artists had become disgruntled with the direction in which art was moving. Many claimed the academy was out of tune with the mood of the times. As a result many young artists took to classes in so-called free art schools, rather than endure the staid, old-fashioned methods of the Royal Academy.

Subsequently, a group with the painter Johan Rohde at its helm banded together to form The Free Exhibition in 1892. Twenty-three years later, Grønningen was put together by a number of these ‘free’ artists rebelling against the original movement.

Grønningen’s aim was to push art to the limit. Grønningen artists, such as Harald Giersing, Olaf Rude, Edvard Weie, William Scharff and Jais Nielsen, began experimenting with Cubism during World War I.

The movement became more and more experimental, constantly pushing the boundaries of public perception and expectations. When the young Vilhelm Lundstrøm exhibited in 1918 with tree stumps mounted onto his canvases, critics moaned that now finally the concept of art had gone beyond all limits.

Fabulous Freddie

In the years that followed, other techniques were explored awakening such controversy and shock that exposed rear ends seemed like positive child’s play.

One of the nation’s first surrealists was the painter Wilhelm Freddie. In 1937 some of his works were shown at an exhibition in a gallery on what is now Copenhagen’s pedestrian street, Strøget.

In the public’s eye this was the last straw. Freddie’s dream-like scenes using sexual imagery “were nothing less than pornographic”. Just two days after the exhibition opened a band of police officers arrived and arrested Freddie and confiscated his beloved, yet controversial artworks.

The ‘offence’ cost Freddie, who was later to become a professor at the Academy of Art, his freedom for three days. The captured paintings were never returned but instead went on display at the Museum of Criminality for the next six years – in what became in its own right a popular exhibition – alongside an impressive array of murder weapons.