Business & Education

From København to Kabul via Mongolia: Denmark’s last explorer

This article is more than 8 years old.

Henning Haslund-Christensen was one of this country’s last true explorers, making his mark in central Asia in the early 20th century

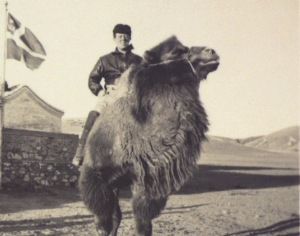

Henning Haslund-Christensen in Mongolia (photo: Nationalmuseet)

Back in 2002, one Dane’s very personal pilgrimage to Afghanistan made for stirring news. Søren Haslund-Christensen, the marshal of the Danish Royal Court, travelled to the volatile region documented by his son, film producer Michael, in a bid to see the grave of his father, explorer and ethnographer Henning Haslund-Christensen, who died in Kabul in 1948 and was buried in the city’s only Christian cemetery.

Until 2003, Søren Haslund-Christensen made his living as a prominent man whose attention to detail and protocol required a subdued presence: the eternal organiser and right-hand man of the queen, devoted to the service of this country’s much-loved Royal Family. For Haslund-Christensen, as he told Berlingske Tidende back in 2002, the journey to Afghanistan was an intensely personal experience – more so because he was able to share it with his son. The court marshal visited the cemetery for the first time in April – the very first opportunity afforded him after 23 years of crippling war in Afghanistan. For his first visit, Haslund-Christensen commissioned a new headstone for the grave, reading simply: “The Danish explorer Henning Haslund-Christensen, 1896-1948.”

At the time of his death in 1948, Henning Haslund-Christensen represented the adventurous dream of many a Danish child. His books, radio lectures, and articles chiefly documented his adventures in Mongolia and brought him great renown in this country, though he failed to achieve the iconic status of someone like Knud Rasmussen. Haslund-Christensen was no Indiana Jones: he was an inquisitive, self-taught researcher who optimised his expeditions by using the cream of the world’s crop of scientific luminaries and favouring far-flung destinations. The purpose of Haslund-Christensen’s journeys was to document indigenous ways of life before the encroachment of other, modern civilisations.

Broken hearted

The head of the ethnographic department of the National Museum, Kaj Birket-Smith, told Berlingske Tidende: “After the death of Knud Rasmussen, Haslund-Christensen was the one person who contributed the most to the growth of the ethnographic collection here at the Naitonal Museum.”

The explorer died in 1948 in Afghanistan, acting as leader of the Danish Central Asian Expedition, after reportedly suffering a heart attack due to overexertion while mountain climbing. The sudden death came as a shock to his then 15-year-old son Søren.

“I remember I was going to school at Herlufsholm when I was suddenly called to Copenhagen. I had a feeling that something was wrong. My suspicions were confirmed as I crossed the Town Hall Square and looked up at the Politiken billboard to see the news that my father was dead up in lights,” Haslund-Christensen recalled.

A father’s son

The death of the noted explorer in a far-off place made it particularly hard for his son to deal with, though Søren Haslund-Christensen learned not to dwell on his father’s frequent, extended absences from the family during his many expeditions.

“Of course my father was away for long periods of time. But he was always with the family very strongly in spirit … I used to get a flood of questions in school about my father, which always irritated me to no end. But he was also a man who came into people’s living rooms – he was one of the first people to hold lectures broadcast on the radio, using recordings from the far-off places he visited,” Haslund-Christensen told Berlingske Tidende.

Søren Haslund-Christensen owns a wealth of archival material and memorabilia about his father and his first book on his father, ‘The Man in Mongolia,’ was issued in 2002.

Søren Haslund-Christensen has also done his part to contribute to the rehabilitation of the country his father died exploring. He was a former member of the Danish Afghanistan Committee, which operated hospitals and clinics in the country.