Business & Education

Wilhelm Freddie: a portrait of the artist as an outlaw

This article is more than 9 years old.

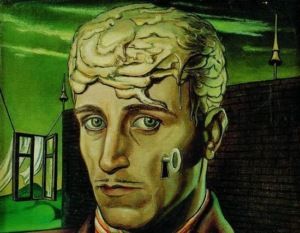

Surrealist outlaw: this country’s answer to Salvador Dali, Wilhelm Freddie was at the very forefront of the Surrealist movement in Europe. But notoriety didn’t come cheap, and Freddie ultimately paid the price for public hysteria

Having weathered decades of public outrage towards his art, Freddie received Denmark’s highest cultural honour, the Thorvaldsen Medal, in 1970 (photo: Wilhelm Freddie)

To be unappreciated in one’s own lifetime – a clever lament that only goes halfway in capturing the long life and work of Wilhelm Freddie, one of the lions of 20th century Danish art. Together with Ejler Bille and Richard Mortensen, Freddie steered this country into the thick of the Surrealist movement. His work was featured at some of the most critical exhibitions of the age, but success was far from sweet from the Copenhagen-born artist. Scandals, public outrage, and charges of criminal obscenity dogged Wilhelm Freddie at the very peak of his career, and despite his long, fruitful artistic output, Freddie’s name would become synonymous with a figure that a paid a high price for greatness – paid too much, perhaps, for the public’s meagre understanding of modern art in the early 20th century.

Freddie was born Frederick Vilhelm Christian Carlsen in 1909, in Copenhagen, the oldest son of a working-class family. He was a precocious child fond of drawing, and drew early inspiration from the works of Futurist Gino Severini and the Danish-born artist Eugène de Sala, who ultimately became his mentor. It was de Sala – born in Randers with the rather inauspicious name of Oswald Simonsen – who made Freddie’s fateful introduction to Surrealism, with the works of Giorgio de Chirico.

Wilhelm Freddie’s early artistic output in the 1920’s was characterized by a giddy, insatiable thirst for different genres. He devoured Cubism and churned out abstract still-lifes. In 1929, Freddie stumbled upon the world of Surrealism, and was immediately turned on to its phantasmagoric images and weighty manifestos. Already, the Copenhagen artist could feel the yoke of artistic limitation waiting to be broken.

Freddie flabbergasted

In 1930, at just 21 years of age and one year after his professional debut, Wilhelm Freddie featured his first Surrealist paintings at the Charlottenborg Autumn Exhibition. One year later, Freddie’s images of twisted, nude bodies in artificial landscapes, fashioned in absurd poses somewhere between fornication and butchery, had so incensed the art-going public, that offended spectators took the paintings down and turned them to the wall virtually every day of the exhibition.

Throughout the 1930’s, scandal followed Wilhelm Freddie everywhere he went, despite the fact that his paintings were featured on a par with the artistic heavyweights of the age: Dali, Tanguy, Miro, Giacometti – Freddie was by turns the underdog and the baddest of them all. It was not unusual for the man on the street to express casual confusion at the insular art world, but this country’s press was unusually merciless to Freddie.

In 1930, daily newspaper Morgenbladet reprinted Freddie’s relatively tame work, “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity,” under the headline “A Modern Artist’s Scribble,” and scoffed, “Dear Readers: what does this picture mean to you?…It MUST be a joke!” By 1935, the public’s ridicule had turned to police action. After participating in an Oslo show where a local MP tried without success to have his paintings removed, Danish police forcibly removed Freddie’s works from the window of a Copenhagen art gallery. The next year, Freddie was invited to participate in the prestigious “International Surrealist Exhibition” at London’s New Burlington Galleries, but English customs authorities refused to allow his baroquely graphic painting, “Psycho-Photographic Phenomenon: the World War’s Fallen” into the country due to laws prohibiting the trafficking of pornography.

Highest honour

In 1937, police seized three of Freddie’s works from a private exhibition in Copenhagen. Freddie was formally charged with three counts of distributing pornography, and fined 200 kroner. But Freddie didn’t lose his audience – all three paintings were hung in Copenhagen’s Police Museum, where they remained until 1963.

The upheavals of the 1960’s did a great service to the public’s understanding of Freddie as a renegade artist – though he never quite managed to live down the scandals of his early years. An interview with daily newspaper Politiken to mark Freddie’s 60th birthday in 1969 was printed under the headline, “I Am Not A Pornographer.” Meanwhile, Wilhelm Freddie continued his prodigious artistic output, coupling the erotic edge of his early works with subtler composition and historic artistic references. In 1970, Freddie received the country’s highest cultural honour, the Thorvaldsen Medal.

The 1970’s would be Freddie’s breakthrough decade, with a host of artistic triumphs and an honoured role as a professor and mentor at the Royal College of Art in Copenhagen – and his works, once reviled by an angry public, were featured as murals on the sides of Copenhagen buildings (one notable example was part of a neighbourhood beautification project on Baron Boltens Gård). Wilhelm Freddie died in 1995, after seven decades of daring artistic achievement.