Business & Education

The greatest Danish composer America ever had

This article is more than 9 years old.

Interest in Denmark’s Golden Age has sparked a revival in the fortunes of Asger Hamerik, the long-neglected late romantic composer who was in his lifetime one of the best known Danish composers outside of his own country

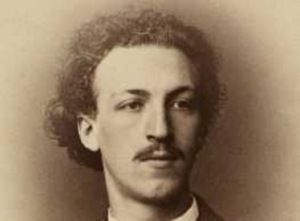

Asger Hamerik left Copenhagen in 1863 after receiving encouragement from Hans Christian Andersen (photo: Royal Library)

Asger Hamerik (1843-1923) studied music under such luminaries as Niels Gade, the most important Danish composer of the 19th century, the famed German pianist and conductor Hans von Bülow and the great French romantic composer Hector Berlioz, before travelling to the United States to become the head of the Peabody Institute in Baltimore, a post he held for almost 30 years.

It was in America that Hamerik composed the bulk of his music – some 41 opuses comprising seven symphonies, four operas, suites, chamber and choral music – whilst hobnobbing with some of the greatest names in music and the arts. Such was Hamerik’s success in the New World that he was trumpeted as the No 1 American composer, although his style is distinctly Nordic with clear links to Gade and Berlioz.

Hamerik’s symphonies all have titles in French. From his mentor Berlioz he adopted the use of the idée fixe – a recurring short melodic strain or motif (the forerunner of Wagner’s leitmotiv), a device in particular evidence in Symphonies No 3 (‘Symphonie Lyrique’), No 4 (‘Symphonie Majestueuse’) and No 5 (‘Symphonie Sérieuse’). Hamerik’s mighty ‘Requiem’, composed in 1887 while the composer was on holiday in Nova Scotia, is deemed his masterpiece.

Berlin to Berlioz

Born in 1843 in Frederiksberg, Hamerik studied the piano with such established composers as Gade and JPE Hartmann. With the encouragement of Hans Christian Andersen, the fairy-tale author and letters of introduction from Gade, Hamerik left in 1862 at the age of 19 for Berlin, where he studied under the great Hans von Bülow, a pupil of Liszt and acolyte of Wagner, and met musical giants of the day including Anton Rubinstein, Berlioz, Franz Liszt, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and Wagner.

Denmark’s loss of Schleswig-Holstein to Germany in 1864 soured life in Berlin for Hamerik, who in protest changed his surname to the more Danish-style Hamerik from the original Hammerich (a German spelling) and quit Berlin for Paris.

Hamerik studied orchestration in Paris with Berlioz from 1864-69, the French composer’s final years, building up a relationship of privilege with the ailing French composer. Times were hard for the ageing Berlioz: his second wife Marie Recio had died in 1862 and his greatest work, the opera ‘Les Troyens’ – staged in truncated form at the Théâtre Lyrique in Paris in 1863 after many frustrations – was given a mixed reception. At the same time his intestinal neuralgia condition was getting ever more serious, only to be aggravated by the news of the death of his sea captain son, Louis, from yellow fever in Havana, Cuba in 1867 at the age of 33.

Parisian praise

Despite the melancholy setting of their friendship, a close bond developed between the composer and Hamerik, who proudly claimed he was Berlioz’s “only pupil”. The respect was mutual, with the French master describing Hamerik in correspondence as “a young composer of much ardour and talent”. An affinity of temperament, a shared love of the music of Gluck and Gade and a sympathy for gargantuan musical apparatus brought the two together. “Berlioz looks after me day and night as if I were his son,” Hamerik wrote to Gade.

Hamerik’s one-man concert in Paris in April 1865, organised by Berlioz, was a thundering success. On the program were the young Dane’s song ‘Le Voile’ (based on one of Victor Hugo’s poems), his ‘Cello Fantasy’, and excerpts from his opera ‘Tovelille’, the tale of a king’s fatal love for a commoner. Berlioz, overjoyed by Hamerik’s success, commissioned a portrait of his Danish protégé from the painter David Jacobsen, a Dane and student of Pissarro, working in Paris at the time.

It was in Vienna in 1871 that the American consul offered Hamerik the directorship of the Peabody Institute, the conservatory and musical society in Baltimore, and he set off in August 1871 for the United States, which was to be his home for the next 27 years.

Bound for Baltimore

Baltimore quickly took to its new Dane, seeing in him a cosmopolitan musician as well as a sound administrator and teacher.

Hamerik left Baltimore in 1898, settling in Copenhagen with his young American pianist wife Margaret – a Peabody graduate – and four children in a handsome patrician villa in Frederiksberg at Christian Winthersvej 16.

Hamerik kept a low profile during his final years. The music scene in Copenhagen was totally transformed: Gade had passed away, Carl Nielsen held total sway in Danish musical circles and Asger felt estranged in his home country after his many years abroad.