Business & Education

The father of Danishness (whatever that means)

This article is more than 9 years old.

Enrico Mylius Dalgas – one of the fathers of ‘Danishness’ who helped shape Denmark’s national identity – died 110 years ago. A great Danish nationalist, Dalgas was actually of immigrant French Huguenot origin

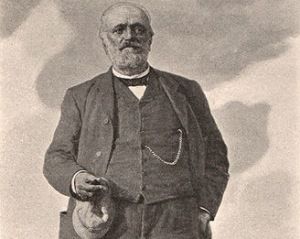

Enrico Mylius Dalgas as he was (photo: August Jerndorff)

It all started in 1864 following Denmark’s crushing defeat in the war against Prussia, which resulted in the loss of a third of all Danish territory and two-fifths of the population. But all was not lost. In Denmark’s darkest hour an astonishing recovery was staged based on the motto “What was outwardly lost shall be inwardly won” – the concept of a wartime officer, Colonel Enrico Dalgas (1828-94), a descendant of the Huguenot family.

Dalgas organised the Danish Heath Society and its large-scale cultivation of Jutland’s heaths, turning vast areas of barren wasteland into forest as part of the national effort to get Denmark back on its feet after the war. Dalgas’s project, along with the efforts of priest, poets and folk high school (close relation of the efterskole) founder Nikolaj FS Grundtvig, gave Danes back a feeling of national pride, instilling in them a sense of quintessential ‘Danishness’. By cultivating the values and traditions of what Grundtvig called the heart of Danishness, Denmark could remain Denmark despite its political subjugation.

‘Danishness’ remains very much a force today in a little country that is more of a tribe than a nation. As James Mellon, a British ambassador in the mid-1980s, noted: “The Danes are a tribe enjoying a shared inner strength and homogeneity that no nation could ever achieve. The most important element in the Danish political system is consensus.”

Jantelov in jest

This nation also possesses a discreet sense of superiority, as university professor Jesper Hoffmeyer wrote in Politiken newspaper: “Danishness can develop into a sort of inverted arrogance based on Dalgas’s famous slogan. No real Dane would of course ever dare say it out aloud, but in their souls, Danes are convinced that, deep down, they really are superior to other bigger nations … We Danes hide our sense of greatness behind a Lilliputian facade.”

Denmark’s lukewarm attitude to membership of the European Union can be seen as the consequence of its tribalism, combined with Grundtvigianism. As Bertel Haarder – now culture minister – once wrote in ‘Liberal’ magazine: “Danes blame everything on the southern Europeans, whatever the problem is. Nazism, wars, rabies, EU directives, corruption, drug-trafficking, foot & mouth, you name it, it is always the fault of the southern Europeans.” Grundtvig himself saw the Danes as a chosen people and lauded Nordic ‘freedom’ and the superiority of the Nordic races over the Slavic and Latin peoples .

Since the fall of communism, Denmark has experienced a crisis of national identity, “crawling back into its shell like a snail”, as Haarder put it, fearful of becoming a multi-ethnic society in an ever-more globalised world, and instead taking refuge in the cosy cocoon cult of hygge. The identity crisis of the 1990s sparked the birth of the ultra-nationalist, anti-immigration Dansk Folkeparti (DF) and the revival of the ‘Danishness’ issue.

Rise of Pia and DF

Tight immigration policies have been imposed as Danes see the future of ‘Danishness’ increasingly in jeopardy. At the first reading in Parliament in 2002 of a bill to permit the naturalisation of a fresh batch of foreign residents, Søren Krarup, a priest and Dansk Folkeparti MP at the time, argued: “Danes are increasingly becoming foreigners in their own country. Parliament is permitting the slow extermination of the Danish people.” He predicted that “our descendants would curse” the politicians responsible for the “alienation of Danes in Denmark”.

Not that all Danes buy into this Danishness. The film director Lars von Trier ran a protest campaign against Dansk Folkeparti and the national mood of xenophobia in the run-up to the 2001 general election, which was fought on the issue of immigration. “The Dannebrog [Denmark’s national flag] is the Danish swastika, it should be burnt,” Von Trier ranted. But it was to no avail; the Dansk Folkeparti emerged as the third biggest party, winning 12 percent of the vote. “The term Danishness reflects the Dansk Folkeparti’s growing importance; it is the ugliest word I have ever heard,” said actress Paprika Steen, whose mother was American.

In his book ‘Last History of Denmark’, historian Søren Mørch wrote the obituary of Denmark as a nation state, seeing nationalism reduced to a farce acted out by boozed-up football fans daubed in the red-and-white colours of the Danish flag. Maybe theology professor Johannes Sløk, a scholar of Kierkegaard, was right when he said: “There is really no such thing as Danish identity. Our roots lie in Ancient Greece, in Rome and in France. Danish identity is rye bread, boiled potatoes and thick brown gravy.”