Business & Education

Opening wide Panduro’s box of tricks

This article is more than 9 years old.

If people’s entire careers were mapped out from an early age, one of Denmark’s most beloved writers might never have published a single page. As it is, Leif Panduro’s literary success was dentistry’s loss

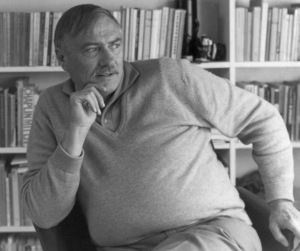

Panduro lived constantly with a fear that he would inherit his mother’s schizophrenia. Turns out he should have been worrying more about his dodgy ticker (photo: Gyldendal)

Contemporary Danish drama owes much to the writers of the pioneering series of the 1960s and 70s. Neither the much acclaimed crime series ‘Ørnen’ (the eagle), nor the popular ‘Taxa,’ not to mention the now-classic ‘Strisser på Samsø’ (island cop) might ever have been made had it not been for shows like ‘Rundt om Selma’ (all about Selma) from 1971, ‘I Adams verden’ (in Adam’s world) from 1973, or 1977’s ‘Louises hus’ (Louise’s house).

Yet all these television dramas were expertly scripted by a man whose tools of the trade were not a pen and a typewriter, but a scalpel and a plaque remover.

Leif Panduro – who was also an accomplished novelist, most notably thanks to the success of his 1958 book ‘Rend mig i traditionerne’ (kick me in the traditions) – was originally trained in dentistry. Indeed, he spent many years scraping the plaque from the nation’s teeth and filling its cavities, both in private practice and from 1956 to 1962 as a school dentist in Esbjerg on the west coast of Jutland.

A Leif changer

He even met his wife, Esther, with whom he had two sons, whilst studying the trade, and they worked side-by-side in the same practice for many years. His first book was actually a humorous look at the profession, wittily entitled ‘Av, min guldtand’ (ow, my gold tooth), which came out in 1957.

After leaving the dentist’s chair behind, Panduro worked in journalism and wrote television reviews for national broadsheet Politiken for a short while, before penning a regular column entitled ‘Panduro mener’ (in Panduro’s opinion). And yet here was a deeply-troubled man plagued by heavy drinking and black, violent moods, a heavy smoker whose poor lifestyle quite probably led to his early death, and a person who – despite his huge popularity – could never simply shrug off a bad review, wrestling instead with inner-demons throughout his entire life.

Panduro lived constantly with the fear of inheriting the psychiatric illness that had so afflicted his family. His mother, for example, spent his childhood on and off in psychiatric hospitals before being admitted permanently with schizophrenia. Born on 18 April 1923 in Frederiksberg, his parents had divorced when he was just three, resulting in his mother reverting to her maiden name, Panduro, which she also passed onto her son.

From dentistry to drama

He spent his unhappy childhood in foster homes, with an uncle, and finally at a boarding school in Birkerød, north of Copenhagen. The final act of his traumatic family history came during World War II, when his estranged father, Herr Petersen, attempted to re-establish contact. Herr Petersen was now a Nazi.

To many, Panduro’s own blend of humorous observation and sharp social commentary was at least in part a way of trying to deal with his own personal demons. His contribution to television drama throughout the ‘70s, mainly in collaboration with director Palle Kjærulff-Schmidt, helped to refine a genre still in the making. It continued right up until his unexpected death on 16 January 1977, leaving a void in his wake. Along with English contemporaries such as Mike Leigh, Ken Loach and Alan Bleasedale, Panduro was one of the leading dramatists of his generation to map the social nuances of post-war Denmark.

Dentists may not be known for their literary flair, but with his books still very much in print and his television dramas still being aired, Leif Panduro can rest easily knowing he will be remembered for his words – not his teeth.