Business & Education

Surviving 300 years of Great Fires, World Wars and sloshed sailors

This article is more than 9 years old.

Hviids Vinstue in Nyhavn is the country’s oldest bar. Restrictive laws and the wear and tear of three centuries have done their best to close it, but it keeps on serving

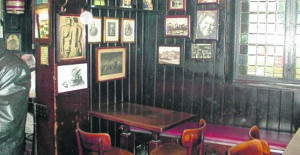

The great establishment itself (stock photo)

Copenhagen is famous for its basement bars. The iconic Nyhavn harbour, which for many tourists is the singular image evoked by the mere mention of our beloved city, is lined with several such drinking holes, many of which are owned by the big breweries.

However, if like me you find yourself hankering after a ‘real’ drinking experience, you could do worse than Hviids Vinstue on the corner of Lille Kongensgade and Kongens Nytorv.

This is not a bar review!

Before you label this article a bar review and berate its poor placement in the history section, consider this: established in 1723, Hviids Vinstue is the oldest wine bar or beer tavern in Copenhagen.It has born witness to both the Great Fires of 1728 and 1795, two wars with England in 1801 and 1807, the First World War and the five-year Occupation during the second. Next decade, the bar will celebrate its 300th birthday.

Decorated in dark wood and lit by candles, Hviids Vinstue makes the mere act of entering the bar a transformative experience that effectively takes a punter back in time.

It’s filled with paintings of numerous intellectuals, writers, artists and actors from the nearby Royal Theatre (the parents of celebrated 19th century actress Johanne Luise Heiberg supposedly met in the bar), many of whom have enjoyed each others’ company drinking in these atmospheric rooms.

The decorative artefacts help to create a sense of a Copenhagen history that lives, breathes and reaches out from every shadow.

Lethal legislation

Towards the end of the century that saw the establishment of Hviids, a new law was introduced that threatened its existence.

Overdådigheds indskrænkning (roughly translated as ‘restricted luxuries’) was an ill-advised 1783 policy, originally intended to encourage the purchasing of domestic goods as opposed to imports and to cut down on the use of foreign labour, thereby boosting the economy. It placed limits on all sorts of goods, from clothes to food.

Those in the catering professions were particularly hard hit. The number of ingredients for those preparing meals became severely limited, but for a bar in the Scandinavian climate that had built a reputation on wine imported from warmer European climes, this new policy was a potential death sentence. How were they supposed to cater to a clientele whose loyalty depended on the product they were forbidden to acquire? They would surely go bankrupt, doing little for themselves or the economy.

Widely regarded as a thoughtless, unprecedented assault on the nobility of wine-sellers, the introduction of Overdådigheds indskrænkning was followed by consistent lobbying for an immediate revocation.

Not yet known as Hviids Vinstue, the bar operated as a tavern for half a century, and it was clear that a couple of defiant French merchants were enabling the business to run in plain sight, despite this being a violation of the new law.

Ultimately, good sense prevailed when the tavern became one of the few for whom certain exceptions were made, and their business was legalised.

Thanks to the thespians

It played in the tavern’s favour that it didn’t resemble any of the more unsavoury establishments down in the harbour or the centre of town.

An air of respectability was maintained largely by way of a shared clientele with two theatres: the Lille Grønnegade-teatret and of course Det Kongelige Teater, which is situated just opposite. Reportedly, women could frequent the bar unaccompanied, seldom raising so much as an eyebrow.

Since its legalisation, the tavern has been doing business consistently without hindrance from the government.

Drunks never change

An esteemed Norwegian playwright, philosopher and historian of the time, Ludvig Holberg, observed that “older Danes have taken to amusing themselves by spending evenings in wine houses, getting increasingly drunk and lambasting what they perceive as the errors of youth on display. They do this until near death or drowning and it is necessary for them to be towed home.”

While this is likely to be a fair observation of many of Copenhagen’s watering holes, it is also indicative of the reckless manner in which proprietors would ply their punters with booze until they were broke or broken. Apparently this little tavern broke the mould by cultivating a reputation for serving guests in a more responsible manner.

Blessed by Bacchus

In 1763, the owner at the time tore down the original timbered house and erected the current building, setting up residence in the floors above the sparsely furnished basement. The bar continued to function throughout.

Through an endless list of disasters and mishaps, the devastating fire of 1795 and the relentless bombing assault from the British in 1807, the basement continued to serve drinks, as though Bacchus himself were divinely intervening to protect the tavern − a place of worship to the wine god.

The importance of being Ernst

The place became a mecca for artists and philosophers to exchange their ideas about the world outside while sipping on a rum punch or hot brandy toddy. This was the tipple of choice among liquor lovers before whisky arrived in Denmark during the 1880s.

At that time, the bar was taken over by a wine merchant by the name of Ernst Hviid, and his name has remained with the establishment ever since.