Business & Education

A government of lost turtles: how Lenin remembered Denmark

This article is more than 9 years old.

The founder of the Soviet Union twice visited the Danish capital prior to WWI, finding its farming more inspiring than its politics

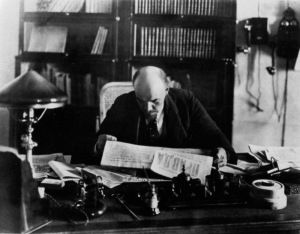

Lenin learnt a lot from the local landowners (photo: Pyotr Otsup, uploaded by Ruslan)

Wasn’t it Winston Churchill who once said that Russia was “a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma”? To be fair, the whole quote speculated whether the key was Russian self-interest, but it fits pretty well with recent events tying Denmark and Russia.

Take Mikhail Vanin, the Russian ambassador, whose unpredictability knows no bounds. Just 17 months ago, he surreally suggested Denmark, under the right circumstances, could legitimately be nuked! And then over the summer, he hosted an event at his embassy to honour Prince Dimitri Romanov – the disputed head of his country’s ‘royal family’, a resident of Denmark since 1960 who many would have thought would be the last person on their invite list.

Churchill didn’t actually say “keep your enemies closer”, but he whispered a version of it to himself sitting alongside Joseph Stalin at the Yalta Conference in 1945.

The contrast is indicative of how relations between Denmark and Russia have developed over the past century. Rooted in a historical context, from Peter the Great’s ascension of the Round Tower in 1716 to the ‘liberation’ of Bornholm, the shared Danish-Russian experience has a bittersweet fragrance.

Licence to Ilyich

During the late 19th century, relations between Denmark and Russia were at a high. A potent royal connection had been established in 1883 when Tsar Alexander III married the Danish princess Dagmar (known in Russia as Maria Feodorovna).

The Russian Royal Family, first Alexander III and then his son Nicholas II, were fond of visiting their in-laws in Denmark and they often summered in Copenhagen along with their children.

But someone else had also paid a visit to Denmark: the leader of the future Bolshevik revolution and the man who would ultimately lead to the demise of the Russian Royal Family: Vladimir Ilyich Lenin.

Life on the move

The life of Lenin was filled with international assemblies and addresses. From the day he gave up studying law to become a Marxist at the age of 17 to the day he took power in Russia more than two decades later, Lenin travelled and lectured all over Europe.

His reasons were simple enough. Known in his native Russia as a revolutionary of long standing, the czar’s secret police were always searching for Lenin. Thus he and his wife, Nadezhda Krupskaya, were constantly on the move, travelling from country to country using pseudonyms, taking little more than the clothes on their backs.

At the same time Lenin was constantly in touch with his newly-founded Bolshevik Party in Russia. Driven underground in St Petersburg, Lenin’s followers relied on their leader’s letters, communiqués and treaties to keep them organised and inspired. Because of this, Lenin’s letters include no fewer than 28 addresses written in 13 separate countries.

Underground success

For the card-carrying Communist romantic, Europe at the beginning of the 20th century was the place to be. From London and Paris to Berlin, Helsinki and Copenhagen, in almost every major city socialist groups and gatherings flourished.

Often outlawed but rarely suppressed, these meetings brought together various socialist factions, allowing them to exchange their ideologies concerning the new century – a century they believed would belong to socialism.

In meeting halls such as the Odd Fellow Palæet in Copenhagen, political catchphrases flew as party members debated the historical inevitability of the fall of capitalism and the growth of a proletarian state. It was just such a congress that brought Lenin to Copenhagen on two separate occasions.

Given 12 hours to leave

Lenin’s first visit to Copenhagen was in 1907 to attend the meeting of the Russian Socialist Economist Workers’ Party, which had been banned in their home country. However, wishing to maintain good diplomatic relations with Tsarist Russia, the Danish government deemed the congress illegal, and so the meeting was broken up almost before it started. The Ministry of Justice gave Lenin 12 hours to get out of the country.

Lenin’s second visit to Denmark was longer, although it is questionable how much more successful it was. In September 1910 the 8th International Socialist Congress was held in Copenhagen at odd Fellow Palæet, and this time the state did not object, though it seems that Lenin did.

Wannabe socialists

Lenin had few good things to say about Denmark’s version of socialism. In fact, he wrote that Thorvald Stauning – then head of the Tobacco Labourers’ Union and a future Danish Socialist Party leader – was a “quasi-socialist” as well as “one of the most stingy and mean-spirited class snobs” he had ever met.

It is not known whether Lenin openly declared this at the congress or not, for there he remained a shadowy figure. His limited knowledge of foreign languages prevented him from giving any speeches or participating in many debates. And his more extreme ideas isolated him from many of his Western peers, whom he later deemed “pseudo-socialists”.

Inspired by Danish farmers

What Lenin did do in Copenhagen was go to the King’s Library. Rain or shine, Lenin would march over to the library each morning and voraciously read Danish agricultural statistics. Though he had nothing but scepticism and disgust for the socialist party, he did admire the impressive productivity of local farms. It seems likely that many of the agricultural programs he implanted in the early Soviet Union were inspired by what he found in the records of the King’s Library.

Finally, it was Lenin’s landlady who remembered the oddest detail about his stay here. “I never even knew who he was,” Vognmand Petersen confessed years later. “He was quiet and kept to himself. But one day, I remember him falling down in hysterical laughter about a dish I was cooking.”

Apparently, Petersen was fond of preparing mock turtle soup, ‘forloren skildpadde’. She asked Lenin if he would like to try some, which the founder of the Soviet Union misheard and instead misunderstood as ‘the Danish government of lost turtles’.

Today, with the contentious Arctic continental shelf boundaries being decided, Denmark stepping up its military presence in the Baltic region and then being left out of Russian-led Baltic security talks, there is little doubt that further misunderstandings are on the horizon.