Business & Education

Decline of Norse a lesson for modern Greenland

This article is more than 9 years old.

While Denmark’s 200-year ownership of the world’s largest island might soon come to an end, history suggests Greenland could struggle should it choose to go it alone

A missionary packs them in for some preaching – it’s an easy gig when it’s minus 30 outside (photo: Aron of Kangeq)

As an autonomous country within the kingdom of Denmark, the relationship between Greenland and Denmark has always been a complicated one. While many Danes bemoan the amount of governmental expenditure devoted to Greenland, with talks of full independence on the horizon the history of Greenland’s relationship with Denmark is worth revisiting. The inter-connectedness, as well as lapses of it, have characterised the two countries’ understanding of each other since the Viking age.

Greenland today is increasingly geared towards an Inuit identity. In recent years, Danish street names and places have been replaced by Inuit ones, Inuit languages are being promoted, and there is renewed focus on Inuit culture and traditions. With the connection between Denmark and Greenland continuing to wane, few people know that the Inuit’s ancestors in Greenland actually arrived after the Norse explorers, with early Danish and Norwegian settlers inhabiting the island from around 980.

Although not the first to inhabit the island – archaeologists have found settlements dating back to 2500 BC – Vikings from modern-day Norway and Iceland landed on the southern coast of Greenland to find it uninhabited. Legend has it that a famous Norwegian Viking, Erik the Red, fresh from his banishment from Iceland for murder, founded the first Norse settlement on Greenland and spent his three-year sentence exploring the island. After deciding that the settlement needed an appealing name, Erik the Red returned to Norway and spoke of his new ‘Greenland’ in the hope of attracting settlers.

Trade and adventure

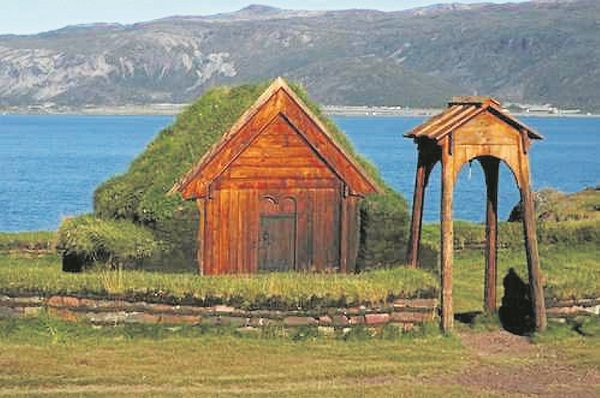

In 985, Erik returned to Greenland with a sizeable number of colonists, establishing two main settlements on the southwest coast, which became known as the eastern and western settlements. In the eastern settlement Erik built the estate Brattahl, near present-day Narsarsuaq, a building of considerable size and stature for the period. Despite the harsh conditions, by the year 1000 a sizeable amount of people occupied the settlements. While some came for a sense of adventure, the settlement grew due to overcrowding in Iceland as well as steady trade between Greenland and the mainland.

Following an epidemic brought by settlers from Iceland, Erik the Red died in around 1003. His death did not deter settlers and it is estimated that at the peak of the Norse settlement, in around 1126, there were between two and four thousand people. Although the colony endured longer than most predicted, its relative fortunes were not to last. A combination of factors, including the Norsemen’s inability to adapt to their surroundings, led to a steady decline in the settlements, and by the year 1350 the western settlement was abandoned. Though the eastern settlement continued for a while longer, nearly all remnants of the colony were gone by the mid 15th century.

One of the contributing factors to their demise in Greenland was the arrival of the Inuit who began settling the island in around 1200. Hailing from the frozen wilderness of modern day Alaska, they were infinitely more equipped to deal with Greenland’s harsh conditions. Utilising a range of hunting techniques – including the use of dogs and sleds – the Inuit were able to capitalise on the region’s marine life, taking advantage of the abundance of whale and seal meat in order to survive Greenland’s winters.

Inuit take over

Although they began settling in the north of the country, there is little doubt that they had contact with the Norseman to their south. While some historians have speculated that Inuit raids led to an increase in conflict between the two cultures, most agree that the arrival of the Inuit was the nail in the coffin for the Norse settlers, because as their numbers declined, the Inuit grew stronger, eventually staking their claim to the whole island.

It can be seen, thus, that even before Greenland became part of the kingdom of Denmark in 1814, a significant history had already been established. The Vikings tried but failed to survive there and were superseded by the Inuit who ultimately fell under Danish rule. This tit-for-tat exchange of ownership and rule has continued into the modern day. When Denmark joined the European Economic Commission in 1973, Greenland drew in the opposite direction, and in 1982 it withdrew from the forerunner to the EU, the only country to ever do so.

Whether Greenland will remain tied to Denmark is a matter of speculation. There’s little doubt that modern Greenland is reliant on Denmark for the provision of essential services such as public housing. In the same way that the early Norse settlers were reliant on the free flow of trade to the mainland, Greenland is similarly tied. Though the country is heading towards an Inuit identity, there is little room for isolation and self-sufficiency in the modern global economy. It’s likely that the coming and going will continue for some time yet.