Business & Education

The day the graphics died: How Ib touched his country deep inside

This article is more than 9 years old.

Anyone who learnt the alphabet reading ‘Halfdans ABC’ will mourn the passing of its illustrator Ib Spang Olsen last month

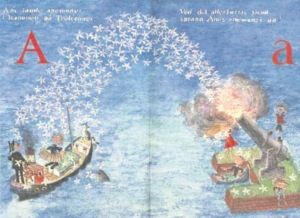

Halfdans ABC is beloved the country over for Olsen’s illustrations and Halfdan Rasmussen’s nonsense rhymes (see top photo) for each letter of the alphabet (photo: Forlaget Carlsen)

The man who coloured in the childhoods of most Danish people alive today is dead. The multi-talented Ib Spang Olsen, who passed away at the age of 90 in 2012, was one of Denmark’s most noted storytellers – but he is probably best known for his drawings in ‘Halfdans ABC’, a book that most Danes growing up over the last 40 years have used to learn to their alphabet.

He belonged to a new generation of illustrators – together with Egon Mathiesen and Svend Otto S – who were highly inspired by Soviet picture book art and had a tendency to include political issues in their work. But while his talent was a vast palette of nuances, it is for his work in children’s books that he is best remembered. Most bookshelves in Danish playrooms and children’s rooms will contain at least one book with his illustrations or scribblings – and the admiration was mutual as Olsen was particularly fond of telling stories to children.

Olsen was born in Østerbro, Copenhagen in 1921, and his upbringing was a modest one. Nevertheless, it was a time that resonated with him, and throughout his career he returned to his childhood memory bank for inspiration for his humorous and often borderline grotesque pencil drawings of everyday life, be it alley cats, playing children or hard-working mothers in kitchen windows.

Natural talent

Olsen’s colourful life as an illustrator began in 1942 as a paper cartoonist at trade union publication Social-Demokraten – today’s Aktuelt – in the Hjemmets Søndag section. This marked the beginning of a very busy career, in which he did around a drawing a day for publication in newspapers, books, and comics, and also for TV and posters.

While his talent was one that couldn’t be taught, he did find time to study, attending the Copenhagen Art Academy and the Graphic School from 1945-1949, and his career actually included a spell as a teacher, at Bernadotteskolen from 1952-1961. He was very much a freelancer!

While Olsen’s preferred working method usually included a pencil, he also used plenty of other different drawing techniques. He used zincography until the end of the 1950s, after which he started using heliographics that made it possible to print the original graphic in book prints and offset. He used his knowledge of different techniques to work in a broad range of different picture genres, from natural observations to book illustrations. And while Olsen is mostly known for his illustrations, he also tried his hand at making ceramics and sculptures, and other indoor furnishings.

Family man

His work was rewarded with several prizes, amongst others the HC Andersen Medal for his drawings, the Ministry of Culture’s children’s book prize three times, and also Gyldendal’s children’s book prize in 2008. You can see some of his work in his gallery that’s placed in one of the small pavilions that encircles the King’s Garden in Copenhagen. Here you can also buy a broad selection of his works.

As Olsen grew older, his production lessened, although he still remained active until the end. Meanwhile, he had other things to occupy his time. He was the chairman of the Ministry of Culture’s working group about children and culture from 1982-1990, and a member of the Academia Council, which is part of the Royal Danish Art Academy.

He also had four children – Tine and Tune from his first marriage, and Lasse and Martin from his second and enduring union to fellow artist Nulle Øigaard. One of his children, Lasse, is a film director and in 2005 started to film a documentary about his father, ‘Det er med hjertet man ser’.

The film is an honest portrait of a man who made a drawing a day for many, many years. Olsen’s position as his country’s most successful and beloved illustrator became even clearer after his death. “It was you, Ib, who brought colour into my childhood. Rest in peace,” said one commenter on Politiken newspaper’s website the day after Olsen’s death. It was indeed the day the graphics died.