Business & Education

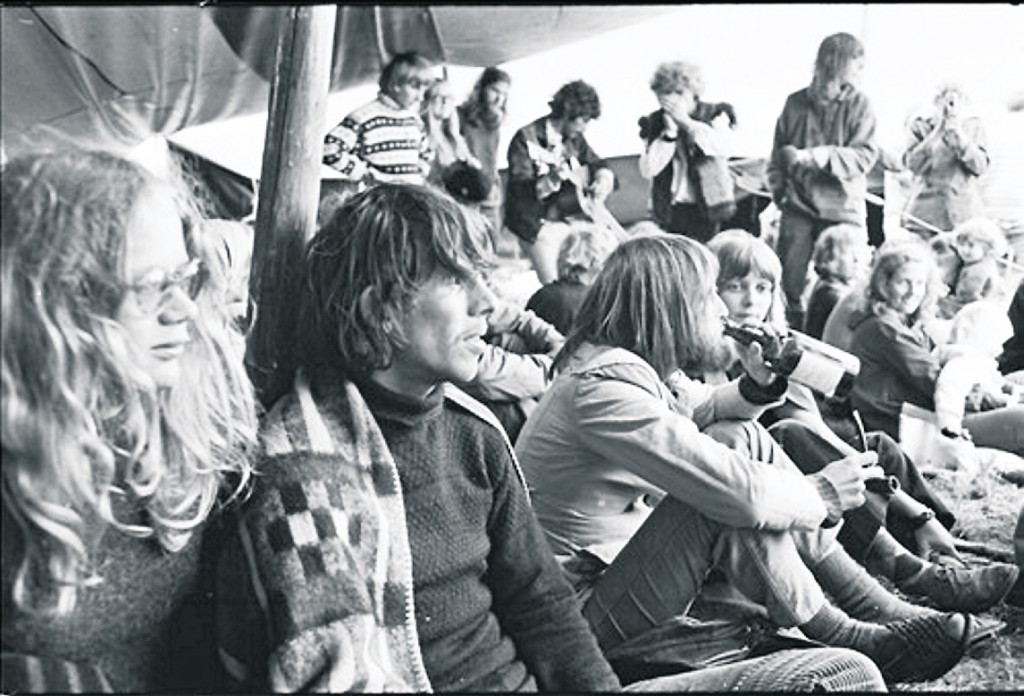

Bad trips, crosses on dicks and angry hicks: Denmark’s Woodstock had it all

This article is more than 9 years old.

In many ways, the extremely lengthy Thylejren Festival was the country’s last hurrah to say goodbye to the 1960s

A last hurrah for the 60’s in Denmark (photo: Thisted Kommune)

As the world watched the mud-covered masses frolicking at the 1969 Woodstock Festival over the Atlantic, the seeds of a similar festival on Danish soil were being planted in the minds of Henning Prins and Leo Jespersgaard, the founders of the grass roots alternative society organisation, Det Ny Samfund. And before long, Denmark would have its very own Woodstock and its very own summer of love.

Finding the right location was proving to be a challenge until a veteran freedom fighter, Leo Kari, turned up at the door of Det Ny Samfund office. Kari, who had fought the fascists both in Spain and in Denmark, just happened to own a sandy and windswept plot of land in the perfect spot in north Jutland and was willing to sell.

Det Ny Samfund jumped at the opportunity: the final deeds were signed in Vestre Fængsel prison where Kari was being temporarily detained on suspicion of cannabis dealing.

A 70-day festival

Wasting no time whatsoever, Henning Prins hurriedly called a press conference to announce the event of the year: a ten-week ‘come-together’ in north Jutland from July 4 to September 15.

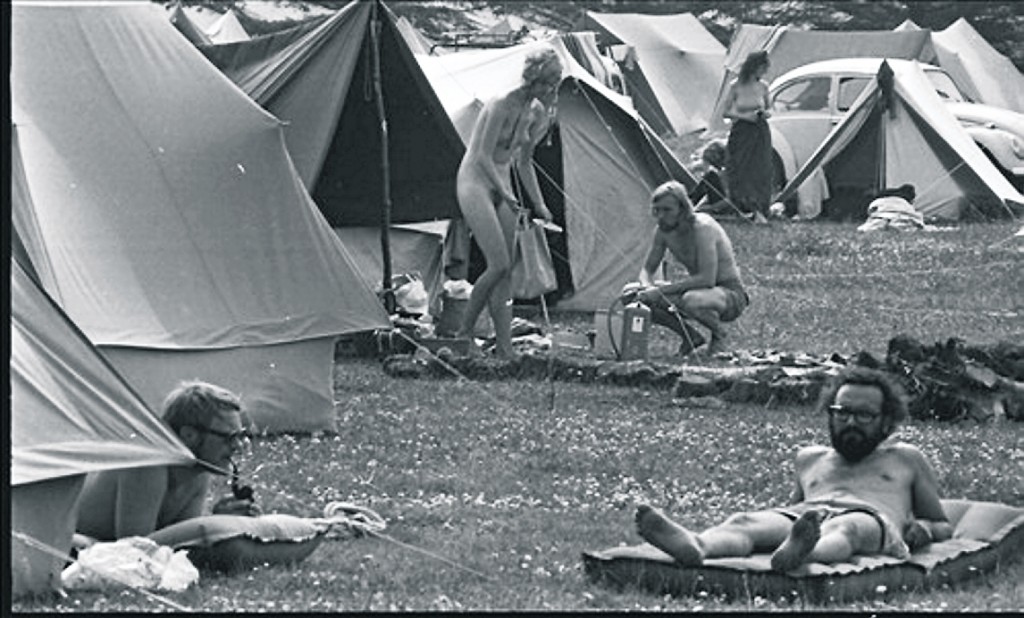

The concept was a do-it-yourself festival where Det Ny Samfund would take care of the practical side of things, with activities and happenings developing spontaneously.

“This will not just be a camp for those with long hair and beaded necklaces,” declared Prins. “Everybody is invited to take part.” A whole variety of groups and people quickly volunteered their services, including one Peter Louis-Jensen, a performance artist from controversial art collective Eks-Skolen, whose group offered an alternative church service – one that was to hit the headlines of the national newspapers and become a small part of Danish folklore.

Hot July 4

So it was, on July 4, that a specially-commissioned love train steamed along the tracks from Copenhagen to north Jutland to the pumping beats of Danish group Blue Sun. Goodness knows what the many curious locals, who turned up at the station to witness the arrival of the colourful long-haired newcomers, made of this noisy, psychedelic spectacle. Initially, at least, there seemed to be an atmosphere of tolerance. The local newspaper, Fjerritslev Avis, humorously described how the local fishermen and festival-goers would meet convivially over a beer to, despite their dialect-based language difficulties, discuss the issues of the day.

“Of course the festival will attract some bad elements,” observed the local mayor, Christian Hansen, to media. “But I think many of the young people from the unhealthy Copenhagen slums will benefit from their stay up here.”

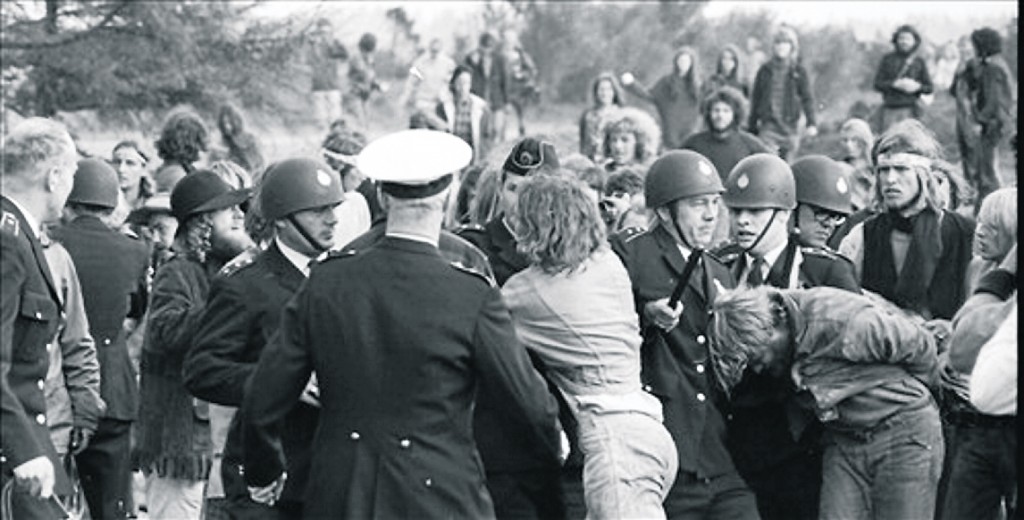

On the surface, the 20,000 guests were living in a hippy paradise, but on festival ‘streets’ like Frank Zappa Lane and Nepal Street, hard drugs were increasingly becoming a problem. A regular item at the common camp meetings was how to deal with those who were having a bad LSD trip. The bow-tied Thisted chief of police, Jørgen Bodenhoff, had taken a softly-softly approach, but was coming under increasing pressure from the national media. Leading the criticism was the tabloid Ekstra Bladet. “The fact is that you can buy red Lebanon and black Afghanistan like others buy Blue Cirkel Coffee in Brugsen,” it complained. A few days later, Bodenhoff succumbed to the criticism and 62 policemen bearing helmets and truncheons headed towards the camp in search of drugs.

Tapping, tip-offs and todgers

The festival-goers had, however, been preparing for this inevitable action for some time, after learning about it via the police radio. At 08:00 on the morning of day 55, a common meeting was called to prepare for the raid. The advanced warning meant that the police only came away with two teabags and a few bruises following some pushing and shoving. Ekstra Bladet, the self-appointed voice of the indignant tax payer, described the raid as a “total fiasco” and a “fantastically chaotic happening”.

But more dramatic events were in store. Always on the lookout to make a political statement, Peter Louis-Jensen, a controversial happenings co-ordinator, had been hatching a plot. Increasingly demoralised by what he saw as a total lack of democracy in the camp, he had meticulously prepared a chaotic happening of his very own.

On day 50, the local vicar Johannes Sørensen accepted an invitation to give a service at 12:30. In the middle of his sermon he was met by a group of chanting activists reciting quotations from Chairman Mao and a naked Louis-Jensen. Nudity was far from unusual at the camp, but Jensen had provocatively decorated his penis with a red ribbon that held a small cross in place.

Who needs the Pussy Riot?

This, though, was just a taste of things to come. Some days earlier, two of the activists had paid a visit to the local Hjardemål church under the guise they were an enthusiastic young student couple fascinated by the wonders of church architecture. Distracting the attention of the church attendant, they managed to make an imprint of the old heavy church key in a piece of bubble gum. A copy was made and the scene was set for the dramatic events of 31 August 1970.

In the late hours, 15 activists barricaded the doors and windows of the church. A sign on the door declared that the parishioners would have to do without the services of the church for the time being and that the church could only be taken back by force. The declared intention of the action was to show “how the powers of the state are built on false authority and blindly accepted and obeyed by the politically alienated inhabitants of Denmark”.

This was the final straw for the long suffering locals and, in a scene reminiscent of the storming of Castle Frankenstein, the church was surrounded. The local vicar, Sørensen, climbed a ladder to act as the voice of reason, but was rewarded with a cry of “fascist pig” and a smashed church window.

I predict a riot

By now the locals were baying for blood and tried to break into the church to teach the activists a lesson. Soon afterwards, 30 riot policemen and a helicopter arrived. In clouds of tear gas, the activists surrendered and were carried out of the church one by one, running the gauntlet of the jeering crowds.

And then, barely moments after the police left the church, a seething group of locals headed towards the festival area to cause widespread panic in the camp. Only police protection prevented the mob from entering the camp: an irony not lost in the national newspapers the following day.

The day after the occupation, a despondent and apologetic camp leadership handed over 5,100 kr oner to the local vicar with the statement: “The camp residents understand the bitterness among the local residents … there has been an affront to the feelings that local people have towards something that is theirs. We understand these feelings, just as we also want that, which we feel is ours, respected − that is to say our camp and lifestyle.”

Time to go, or was it?

The tolerance of Mayor Hansen had by now worn thin. He made it clear in no uncertain terms. “In my opinion, we had to give them the chance to show what they stood for,” he told media. “They got this chance, and I will be the first to admit and regret that our expectations have absolutely not been lived up to.”

A full moon on September 15 ended the festival, and the guests went home, but the camp lived on. Smaller versions of the festival continued each year, and gradually the number of permanent residents increased. Local animosity towards the camp continued, reaching a high point in 1989 when Hanstholm Council refused to pay out benefits to the inhabitants of the camp on the grounds that the people were not of local origin. The government had to step in and set up an emergency welfare office in the local inn. After years of struggle, the area was given a special status similar to Christiania in 1995, with a maximum of around 75 residents allowed at any one time.

The film documentaries of the festival bear witness to an idyllic vision of how the festival was, and for many of the guests, it will have been one of the most euphoric and memorable times of their lives: a glorious summer of love in north Jutland of music, enlightenment and free spirit.

A Prins of men, until it started

But it should be remembered that the festival did not organise itself. In a 2009 interview with Peter Øvig Knudsen, the author of the detailed two-volume book ‘Hippie’, a day-by-day account of the 1970 festival, the charismatic visionary behind the festival, Henning Prins, is still scarred by the events of the festival.

“The months up to the festival were surely the happiest times of my life. It was as if everything just fell into place, despite it being practically impossible to get a festival up and running in a few months,” he recalled. “But we were a generation in love with ourselves – the camp itself was my life’s disappointment.”

Forty years on, he is still bitter about what he sees as the conspiratorial role played by church squatter Louis-Jensen. He feels that he was involuntarily thrust into the position of camp general and that Louis-Jensen took advantage of this to sabotage the camp to suit his own political needs.

End of an era

Popular mythology likes to claim that Charles Manson killed the 1960s, but in Denmark, maybe the bizarre happenings at the Thylejren Festival have a stronger case.

Three days after it ended, Jimi Hendrix, who on 3 September had set KB Hallen in Copenhagen ablaze with another classic concert, was found dead in Notting Hill. And then, just four days later, the streets of Copenhagen rocked to the sound of molotov cocktails and broken glass as young revolutionaries protested violently against the World Bank summit.

In Denmark, and further afield, the age of flower power was over, and a different kind of power struggle was just beginning.