Business & Education

Concept catcher in the land of the rye, we salute you

This article is more than 9 years old.

Søren Kierkegaard, the godfather of existentialism, turns 203 today

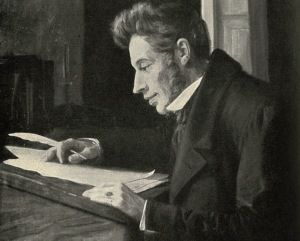

Søren Kirkegaard – influencing greats from Sartre to Heidegger (photo: www.iep.utm.edu)

Today marks the 203rd anniversary of the birth of Copenhagen native Søren Kierkegaard, considered by many to be the pre-eminent Danish thinker and the godfather of the existentialist philosophy that, a century after his death, would run rampant across the Western World.

Though such thinkers as Jean-Paul Sartre and Martin Heidegger would acknowledge Kierkegaard as a leading influence, it is unlikely that they would have been in thorough agreement. Kierkegaard was an ardent Christian who wrote extensively on spiritual devotion, the ultimate test of whether or not to believe in God, and the ungraspable mysteries of the spirit world; these were items for which Sartre and Heidegger would have little use.

However, the Kierkegaardian concern of the significance of personal choice appealed to these existentialists, who essentially viewed life as an absurd condition only given value through the choices an individual makes.

Between two worlds

Kierkegaard spent no small amount of time endeavouring to navigate the murky, subjective terrain of an individual’s consciousness. Though he acknowledged that science can give us truth about the external world, the internal world – an individual’s reality – cannot be objectified, and remains “ever problematical” and “ambiguous”, as related by biographer Josiah Thompson.

From an early age, Kierkegaard was dreamy, detached, and altogether different. “I was always, always outside myself,” he would later say. Coming from many, this statement might be indicative of mental illness, but coming from Kierkegaard, the statement suggests one almost completely absorbed in the private, intimate sphere of one’s own thoughts and feelings. His essence was quite removed from the physical world and its daily bustle. Years later, he would say: “Fundamentally I live in a spirit world”.

This fundamental denizen of the “spirit world” attended the University of Copenhagen and then worked as a Latin instructor at Copenhagen’s Borgerdydskole. Whatever money he was making saw a heavy increase following the inheritance he received when his father died in August 1838. Now relieved of his daily struggle for bread, the young man’s life “took on the shape of an aesthetic hermitage”, noted Thompson.

An outgoing recluse

Though he had reclusive tendencies, he was a well-known character on the streets of Copenhagen, where he took frequent walks – his “immersion in humanity”, as he called it. The city was a “large reception room for him”, where he could be observed engaging in lively conversations with various acquaintances.

Thompson paints an intriguing psychological portrait: “To understand Kierkegaard is to understand the double image of a man who knew many yet was known by none, who chatted with everyone yet really talked with no-one, who made the streets of Copenhagen his own reception room, yet lived in a cloister.”

Even a relatively brief treatment of Kierkegaard would be remiss without a mention of Regine Olsen. They met in 1837 and became engaged in 1840. The following year, Kierkegaard broke off the engagement and then headed to Berlin. Six months later, he was back in Copenhagen, but never made another attempt to resurrect the engagement. Though no exact motive for the split has been established, it is speculated that Kierkegaard felt his often withdrawn and gloomy temperament would make him a lacklustre husband. Looking back on the split years later, he would say: “When I left her I chose death”.

A productive break-up

Though life sans Regine may not have been conducive to Kierkegaard’s personal happiness, the ruptured engagement was to the benefit of philosophy. Relieved of any domestic obligations, he had all the time in the world for contemplation and writing – an activity he pursued about as ardently as one could.

During his most productive period, Kierkegaard generated over 20 religious discourses, along with eight works under a pseudonym. Among these pseudonymous works was the anxiety classic ‘Fear and Trembling’, in which Kierkegaard strove to illuminate the conflict Abraham felt, as documented in the Book of Genesis when God tested his faith by asking him to sacrifice his only son.

For such a prolific scribe, Kierkegaard left behind a curious lack of autobiographical writing. Some might say this makes him more mysterious, and perhaps that was his intention. According to Bruce H Kirmmse’s ‘Encounters with Kierkegaard’, some of the philosopher’s acquaintances thought that he “deliberately cultivated an air of mystery and eccentricity”.

One might say Kierkegaard deliberately cultivated controversy when he published a series of articles full of vitriol against the Church of Denmark, which he perceived as being too bureaucratic and far removed from Kierkegaard’s ideal of “an intensely personal existence lived in imitation of Christ”. The outrage these anti-church articles courted would be the most attention he received during his lifetime. It would also be his final cause.

Transcending via translation

In late September 1855, Kierkegaard collapsed in the street. He was taken back to his residence, and a few days later he was brought to Frederiks Hospital. There his condition would gradually decline over the next 40 days until his death on November 11. The 42-year-old most likely succumbed to a staphylococcus infection of the lungs.

At the time of his death, he had used up almost all of his inheritance and earnings. There was enough money remaining to pay for his funeral, which – owing to his recent bashing of the state church – turned into a crowded, incendiary affair. It is rather ironic that the funeral of such a private man should culminate in furor.

Though Kierkegaard had something of a cult following at the time of his death, his works were given rare mention outside of Denmark and Germany. It was in the wake of the First World War when his popularity enjoyed a significant rise, thanks mainly to his works being translated into English and French.

However, it was following the near apocalypse of the Second World War when his popularity skyrocketed. The biggest new buzz word was “existentialism”, and it seemed every other intellectual began paying homage to Kierkegaard. The lifelong occupant of the ‘spirit world’ was now swarming across the earthly planet.