Business & Education

A crack of light in the darkness that led thousands across the Sound

This article is more than 9 years old.

Celebrations this year will commemorate the 73rd anniversary of the Rescue of the Danish Jews in early October. The Copenhagen Post provides a personal reflection on the 80 captured in Gilleleje who didn’t make it

Gilleleje Kirke has a more harrowing story than most churches (photo: Sarah Anne Freiesleben)

In July of 2013, I walked down the brick aisle of Gilleleje Kirke on the northern coast of Zealand to marry a Dane and effectively unite my heart with Denmark forever. On this personally sacred day, Ulla Skorstengaard, the priest at the small white church in this quaint fishing village, began the ceremony by pointing out that my groom and I, along with all our guests, were sitting within the heart of a story that each church forms through the years.

The audience sat in a still hush, as we were reminded – as is described in the bilingual historical pamphlet found in what they call in Danish the våbenhus (weapon house) at the front entrance of the church – that while many in early October will give thanks and mark the 70th anniversary of the evacuation of the Danish Jews to Sweden, there were also some hard-luck stories, and that one of them took place in this very church.

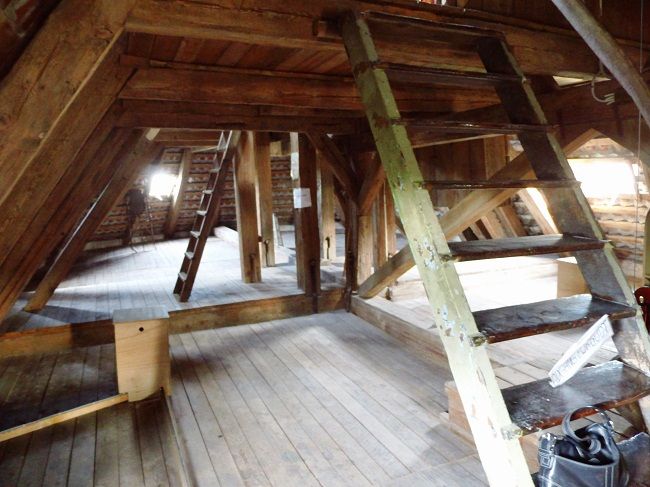

Skorstengaard encouraged the audience to “look up”, and from the pews the guests could observe the hanging ship models dangling from the ceiling of this church as found in many Danish churches. And beyond that is the attic where 80 Jews, who were hiding and awaiting covert assistance to take them over to Sweden, were captured on the night of 6 October 1943.

They were taken by the Gestapo and sent to Theresienstadt, a concentration camp located in the modern day Czech Republic.

Like a wedding in ‘Game of Thrones’

One can imagine the feeling of the multicultural audience as this story was told. Why would a story of such a horrible thing be told at a wedding? This was meant to be a day of joy and celebration. To answer this unspoken question, Skorstengaard borrowed Leonard Cohen’s wise words to give my husband and me the advisory blessing: “Forget your perfect offering. There is a crack, a crack in everything; that’s how the light gets in.”

But what metaphorically positive light, I wondered, standing there in white on the happiest day of my life, was to be found by imagining a large group of cold and frightened people of all ages huddled together in the loft just over our heads wondering if their destiny would be to safely cross Øresund, hidden under the netting of a herring fisherman’s boat, or being forced to board one of the large trains the Gestapo had ready to carry thousands of Jews to Theresienstadt and, possibly from there, on to an organised execution?

Occupation or co-operation

It was only while researching the greater context of the events surrounding this tragic one that I began to appreciate the ‘light’ that the values of the Danish people shone on to one of the darkest events in European history.

Denmark’s mostly peaceful occupation by Nazi Germany in the Second World War, which began in April 1940, remains a subject of much discussion and debate. Like many other European countries, Denmark lacked the arms to successfully fight off a Nazi invasion, but in hindsight, some initial token resistance, however futile, might have more clearly defined the neighbouring countries’ war-time relationship. In addition to Denmark taking the ‘safe’ approach by accepting an occupation with little official resistance, Germany also had an interest in keeping a primarily peaceful relationship with the Danes who were, after all, their Aryan neighbours and could easily be envisaged as citizens of the post-war Nazi German state.

As the war progressed, the boundaries within the Nazi occupation of Denmark became more blurred and many Danes considered their relationship with the regime to be on a slippery slope towards ‘co-operation’. Despite the many grey areas within the Occupation, a clear line for how far the Nazis could reach had been drawn when it came to answering the ‘Jewish question’.

King Christian X had made it clear that no racial legislation or discriminatory measures would be accepted in Denmark, and the Nazis had conceded this matter in light of their interest in keeping a relative peace, their increasing dependence on Danish supplies, and their initial deduction that there was a considerably unsubstantial number of Jews in Denmark, compared to the estimated nine to ten million in Europe. As a result of this combination of reasons, the Jewish population of Denmark had not been registered, nor were they forced to wear the yellow Star of David as they were in other countries.

Nazis riled by rising resistance

However, by 1943, many Danish people had grown increasingly frustrated with the German Occupation and the Danish government’s tolerance. Resistance movements, both civil and violent, were on the rise. By the late summer, fuelled by the increasing number of moral conflicts with the Occupation, illegal publications, acts of sabotage, organised demonstrations and violent attacks on German and Danish officials – which culminated in what is called the August Uprising – Hitler decided it was time to address the situation in Denmark more aggressively.

The Danish government was removed from power on August 29, and in a statement of power, General Werner Best decided to cross the line that had previously been drawn and target the Danish Jews – although he waited until the trade negotiations with Denmark for the following year were settled. The operation was scheduled to begin on October 2.

The good German

Among those Best informed was a German attaché working in Denmark, Georg Ferdinand Duckwitz, who many Danes remember today as ‘Den gode Tysker’ (the good German). He quickly leaked the information, and within just a few days, the word had spread through various channels and networks.

The non-Jewish Danish people formed a grassroots underground railroad initiative, which led to the successful evacuation of around 93 percent of the Jewish population in Denmark. Approximately 7,000 Jews living in Denmark safely made it to freedom. Gilleleje was one of the largest evacuation points and word spread fast that this was an opportune place to attempt the crossover to Sweden.

However, the Gestapo also caught on, and on that fateful night, in early October 70 years ago, the Nazi secret police discovered the largest gathering of Jews found anywhere in Denmark, hiding in the attic of a church.

Never again in the field of human history

In the end, though, relatively few Danish Jews died during the war. The 80 Jews from the attic remained at Theresienstadt and avoided the death camps. And of the approximate 470 Danish Jews who were captured in Denmark, most were rescued later and taken to Sweden where a favourable reception had been arranged through the Swedish PM by Duckwitz.

Elsewhere in Europe, the Jews were not as fortunate. Approximately between one half and two thirds of the Jewish population did not survive the war, and today the Holocaust is recognised as one of the worst atrocities to humanity the world has ever known.

It was a dark moment in human history, and Denmark’s passive involvement did little to help, but as the priest pointed out on our special day, there were some positive cracks of humanity, and the Rescue of the Jews was one such moment.

This personal experience opened my eyes to reflect on the good in human nature that shone through during the atrocities of the time, and it makes me feel proud to live in a country whose people rallied together to form one such small crack. The collective respect for human dignity shown through the unplanned collaboration of Danish civilians was, according to Winston Churchill, “second to none”.