Things to do

A genius getting to grips with greed, gluttony and gin-soaked grubbiness in all its glorious detail

This article is more than 9 years old.

William Hogarth gave us the human condition, warts and all

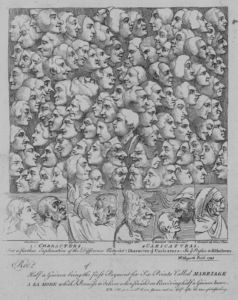

Hogarth’s ‘Characters and Caricaturas’ (all photos: Karen Søndergaard, of the works of William Hogarth)

The power of satirical art to shock, provoke, entertain and promote discussion can hardly be underestimated. A timely exhibition at the National Gallery of Denmark (SMK) brings together a generous sampling of the graphic works of William Hogarth, one of the greatest proponents of this genre.

Hogarth (1697-1764) was a painter, printmaker, satirist, art theorist, entrepreneur, philanthropist, social commentator, moralist and English nationalist. Almost a personification of the mobility of 18th Century society, he rose from lowly origins, married the daughter of his teacher, Sir James Thornhill, and ended up a well-respected man. He succeeded through hard work and talent, rather like the good apprentice in the print series entitled ‘Industry and Idleness’.

The smell of the crowd

Above all, his work provides a vivid snapshot of 18th Century English life – particularly London life – and his depictions of crowds have scarcely been bettered. These are obviously real people, jostling one another, fighting, picking each other’s pockets and exhibiting all the foibles of human individuals.

The exhibition is based around four of Hogarth’s major narrative print series: ‘The Harlot’s Progress’, ‘The Rake’s Progress’, ‘Marriage à la Mode’ and ‘The Stages of Cruelty’. Hogarth was an astute businessman. He realised that good money could be made by selling prints in series through subscriptions. So much so that he was instrumental in bringing in the Engraving Copyright Act of 1734 to protect his work from unscrupulous fakers. As a consequence, his prints were widely known by his contemporaries.

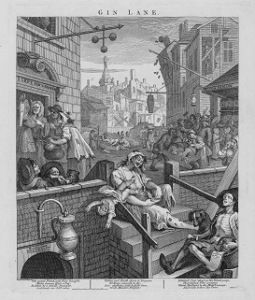

But Hogarth is not just providing a window into the past. His themes of greed, gluttony, sex, violence, drunkenness, cruelty, political corruption and exploitation are equally relevant to us now. Today’s Daily Mail reader will have no difficulty being just as scandalised by the binge-drinking and excesses shown by the lower classes in Gin Lane as Hogarth’s contemporaries were.

Innocents abroad

Then as now, people from the country were drawn to the towns, searching for opportunities and prosperity. Over the course of six prints, ‘The Harlot’s Progress’ charts the journey of an innocent country girl arriving in the metropolis in search of work, to her eventual demise in a seedy garret as a disease-ridden prostitute. The prints also highlight the risks involved in sexual pleasure; venereal diseases were common and there were no reliable cures. In plate 5, two doctors squabble with one another over the relative efficacies of their treatments whilst totally ignoring the dying patient.

‘The Rake’s Progress’ series can be viewed as a pendant to this with a male protagonist. Young Tom Rakewell inherits a fortune and is immediately set upon by spongers and chancers of all kinds. Pretty soon he is living the life of the fashionable libertine, gambling, whoring and squandering his money. Hogarth manages to get some sly digs in here at the perceived corrupting influences of foreign fashions and fads (particularly French or Italian). After further trials and tribulations, including marriage to an ugly elderly rich widow in a bid to restore his fortunes, Tom ends up incarcerated in the Bedlam lunatic asylum.

The devil in the detail

In plate 1 of ‘Marriage à la Mode’, two dogs chained together in the right foreground mirror the actions of the protagonists, whose marriage contract is being hammered out by their respective fathers. The young couple are completely ignoring each other; indeed, the girl seems far more attracted to the handsome lawyer’s assistant who will shortly become her lover, while the young nobleman is only interested in himself. Already here, we can tell that this is going to end badly.

These prints may seem to us finger-waggingly moral at times, but there is a great deal of fun to be had in paying close attention to the details. Everything that Hogarth includes in the pictures, from pets to the pictures on the walls in the rooms, has significance. It is also worth noting the facial expressions of his characters. The heavenward gaze and dismissive gesture of the steward in plate 2 of ‘Marriage à la Mode’ speaks volumes.

As the opening text at SMK so aptly puts it, the prints are there to “entertain, engage our eyes and senses and capture our attention”. Mission accomplished!