Business & Education

The bitter-sweet life of a writer who gave schoolyard bullies their just desserts

This article is more than 9 years old.

There aren’t many people who can claim to have died in a place that bears their name, but this country’s second most distinguished children’s writer is one of them

There was nothing rubbery about Kirkegaard’s ability to crank out brilliant children’s books (photo: Koldinghus Museum)

On the evening of 23 March 1979, a teacher stopped by a small watering hole in Stenderup − a tiny village in East Jutland. After consuming his considerable fill of alcohol, he braved the walk home. Despite the month, winter was still in full swing with freezing temperatures, bitter winds and icy roads to contend with. The alcohol in full effect and the warmth of the bar quickly leaving him, he soon became desperate to find shelter. Only a church stood nearby.

He approached it, but on closer inspection the teacher found the church to be closed and despite his best efforts, he could not gain entrance. Tired and unsteady, he went around the church to find a shortcut home. He was met by snow drifts that prevented him from reaching his house. It was on the lawn outside the church that a gravedigger found the teacher’s body the next morning, frozen. There were marks on the church door where the teacher had tried to kick and claw his way in. Furthermore, the gravedigger recognised the body, telling his wife that he thought it was the famous writer Ole Lund Kirkegaard.

Born in Aarhus in 1940, he was just 38 years of age when he succumbed to hyperthermia that night. He had only enough time to grace us with 13 of his books, which were exclusively written for children, but this was enough to secure his reputation as one of Denmark’s, if not the world’s, greatest children’s authors. He left a legacy of cherished works (both written and illustrated) that will remain in circulation for generations to come and whose reputation in Denmark is rivalled only by those of the great Hans Christian Andersen.

Modern day HC Andersen

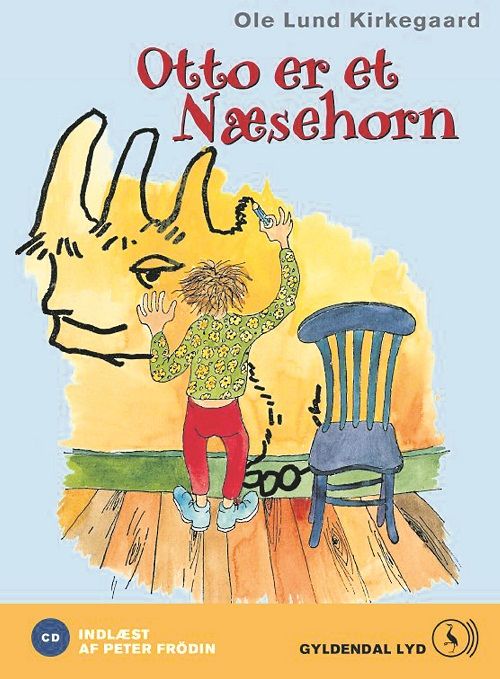

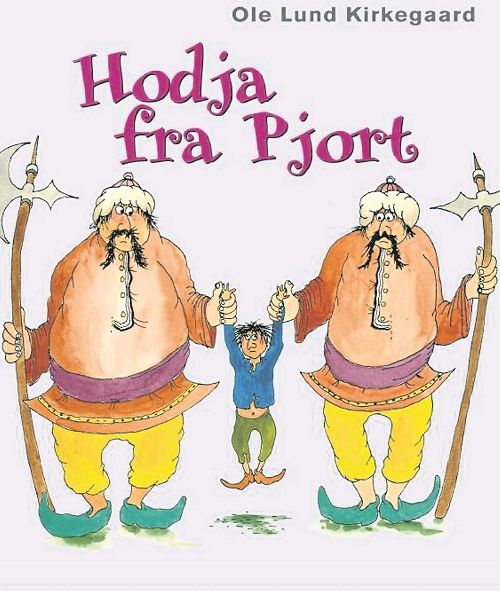

Many of the books have been translated into several languages, while several − including ‘Lille Virgil’ (‘Little Virgil’), ‘Gummi-Tarzan’ (‘Rubber-Tarzan’), ‘Otto er et næsehorn’ (‘Otto is a Rhino’), ‘Albert’ and most recently ‘Orla Frøsnapper’ (‘Orla Frogsnapper’) − have been adapted for the screen.

It all began in June 1966 with an open invite from Politiken newspaper to determine “Who can write the best short story for children aged seven to 15?” Already a teacher at that point, Ole won the competition with ‘Dragen’ (Dragon) and followed it up with ‘Lille Virgil’, starting a long line of successful publications. He remained a teacher until 1977 (after which he went on the road to lecture) and often read out loud his own writing for the pupils, but it was perhaps a strange profession for one who, as a pupil himself, had grown up disillusioned with the school system.

Indeed, many of the antagonists in Kirkegaard’s stories are school teachers or schoolyard bullies. The answer lies in the allegiance he felt towards his pupils; in many ways, he was one of them − rather than a member of the adult world. In fact, much of the conflict that occurs in his books is fuelled by clashes that occur between the regimented adult world and the curious chaos of childhood. He once said of his work, “My main motivation is describing the relationship between child and adult.”

Hero of the bullied

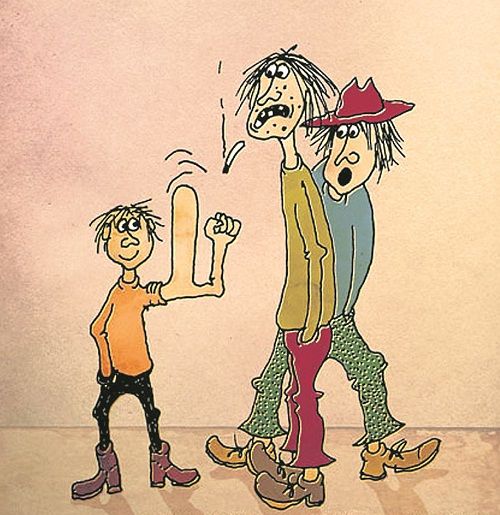

In perhaps his most celebrated work, ‘Gummi-Tarzan’, during a face-off between a teacher and pupil, we find particular contempt for “those who have completely forgotten how it is to be small and scared”. The story of ‘Gummi-Tarzan’ is a classic example of the themes, characters and (crucially) the humour that occur in most of his books: Ivan is a short, weedy loner, he’s constantly bullied by other kids because he’s dyslexic (a condition Kirkegaard himself suffered from), he can’t spit very far and he has no interest in playing football.

To top it all, his father is angry that his stupid, puny son is nothing like his idol Tarzan and accordingly refers to him as ‘rubber Tarzan’. When Ivan meets a witch, she grants him one wish. Without hesitation he uses it to take his revenge on all who have wronged him.

Certainly it would seem that Kirkegaard posits himself as someone who gives voice to the underdog or the loser. He empowers the weak, the lonely and the unloved. All of his characters exist on the periphery of society, often representing the anarchic elements of nature in opposition to the rigorous structures of the imposing adult world.

Outside the box

He rallies against notions of normality, conventionalism and all those who have forgotten how it is to be a child and be full of curiosity and wonder. Often he gives the grown-ups a taste of their own medicine, and he has a particular knack for exposing the absurdities and ridiculous contradictions of adult behaviour.

One might be forgiven for imagining Kirkegaard’s own upbringing was particularly strict, but that wasn’t apparently the case. He had liberal parents, Neils and Ellen, who gave him a long leash at home. He was allowed to do many things that others in the neighbourhood were forbidden to do: their garden was at his disposal and he freely climbed the trees, carved totem poles and once built a miniature circus.

They lived in a small town 25km outside of Aarhus, and his writings indicate a nostalgic fondness for these smaller communities and their inhabitants. The teachers often get a rough ride, but other public servants such as priests, firemen and doctors are represented as kind people who would freely give of their time. The chief of police in ‘Otto is a Rhino’ is one such example.

Unforgiving demise

While his works are brimming with playful humour, there’s an undeniable melancholy that pervades each one. At the time of his death, Kirkegaard had, for only three months prior, been separated from his wife, Anne Lise, with whom he had two young daughters.

Since the split and giving up teaching, his drinking had increased, and although rumours of suicide were quickly dismissed, the impression one gets is that of a sensitive man who fell foul of his own shadow. As well as actually dying in a kirkegaard, it is ironic that he himself should die quite literally as an outsider who for the first time wanted to get inside, in a small village of around 400 inhabitants, much like the ones he affectionately wrote about.

But unlike in one of his books, there was unfortunately no kindly public servant to come to Kirkegaard’s aid that night in 1979 to rescue him in the same manner he would have surely afforded one of his protagonists.

Kirkegaard has mesmerised Danish children with classic like ‘Gummi Tarzan’, ‘Otto er et Næsehorn’ and ‘Hodja fra Pjort’.