Business & Education

Scandinavian grudge match: a rivalry that has cooled but still continues

This article is more than 9 years old.

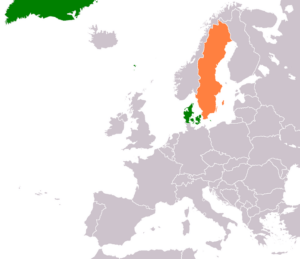

Today Sweden vs Denmark is chiefly a sporting fixture, not dissimilar to siblings striving to better one another, but for many centuries the countries hated each other, endlessly fighting wars and disputing territories

Not a fair fight you might initially think, but then again, Napoleon was no giant (photo: Plumoyr)

Ask any Dane what they think of Sweden and you’re likely to be met with a pause. Depending on who you speak to, this can be followed by a smile, a laugh, the rolling of eyes or even a curse.

Similar to the relationship between Canada and America, or Australia and New Zealand, Denmark and Sweden share a special rivalry that manifests itself in a host of ways, most notably on the sports field like in the recent Euro 2016 playoffs, and also in the odd difference of opinion, as has been seen during the ongoing refugee crisis.

READ MORE: Venstre scolds Sweden ahead of EU meeting

Unlike these other countries, however, Denmark and Sweden’s rivalry is seeded in a time when the countries were vying for supremacy, leading to centuries of war.

Denmark at the peak of its power

Formed by the ruthless political wrangling of Queen Margrethe, Denmark in 1397 pretty much was Scandinavia. With borders stretching from Greenland to the tips of Swedish Finland, Denmark was at the peak of its power.

While the Union of Kalmar – which united the kingdoms of Denmark, Norway and Sweden – was initially agreed under the guise of mutual protection, bickering soon began and by the 1430s Sweden began to want greater autonomy.

In 1523, under the leadership of Gustavus I, Sweden became independent, setting the stage for the problems that would follow.

The Lutheran spell

The impact of the Reformation would be felt heavily in both Denmark and Sweden, and in 1536, King Christian III became king of Denmark, moving quickly to depose the Catholic bishops in Copenhagen.

By 1559, Lutheranism was firmly established in Denmark and Norway, leading to close ties between the Protestant kingdoms that lined the Baltic.

In the Thirty Years War that engulfed most of Europe (1618-48), Sweden was to play a key role, leading to two short wars with Denmark that was to claim the provinces of Jemtland, Herjedalen, Idre and Serna, and the strategically located Danish islands of Gotland and Øsel in the Baltic Sea.

Crossing the (belt) line

With the balance of power shifting, there followed more than a century of unrest, with both Denmark and Sweden competing for influence over the Baltic.

By the middle of the 17th century it was clear that Denmark was losing the struggle.

During the Second Northern War in 1658, King Carl Gustav earned his place in legend by successfully marching thousands of troops over the frozen seas separating Denmark from Sweden.

This famous ‘crossing of the belts’ took the Danes completely unaware, leading to the humiliating treaty of Roskilde in 1658.

Following this, Sweden’s status as a European power was confirmed and they went on to establish trade domination over the Baltic as well as quasi colonies in modern day Estonia and Latvia, as well as parts of Germany.

Unsuccessful reclamation under an inexperienced king

Not content to see their one-time brothers in the ascendancy, the Danes leapt at a chance to attack Sweden again in 1700 in what would become known as the Great Northern War (1700-1721).

Prompted by the crowning of Sweden’s inexperienced King Karl XII, the Danes sided with Russia and Poland-Lithuania, and they together successfully forced Sweden to abandon her overseas conquests.

Although Denmark pushed for the reclamation of her lost territories, this was unsuccessful. However, Denmark was able to begin its claim in the area now known as Schleswig Holstein.

No way we lost Norway

During the Napoleonic Wars a century or so later, Denmark and Sweden were once again on opposite sides. Denmark’s attempt at staying neutral backfired spectacularly when the British considered their attempt at trading with both Britain and France an act of aggression.

The subsequent shelling of Copenhagen by the British Navy pushed Denmark closer to Napoleon – a decision that would have dire ramifications.

Following Napoleon’s defeat in 1815, Denmark was forced to sign the Treaty of Kiel, yielding Norway to the Swedes. Although the Norwegians soon claimed their independence, the loss of Norway was a bitter pill to swallow, more than halving the territory established by Queen Margarethe nearly half a millennium before.

Family bonds

Although there were minor border disputes throughout the 19th century, relations between Sweden and Denmark improved.

As Germany unified and Russia exerted greater influence on the Baltic, both Denmark and Sweden were forced to accept their marginalised places in a new Europe.

Instead of looking at each other with jealousy and mistrust as they had done for centuries, leaders in both Denmark and Sweden began to look for shared interests and values, leading to renewed interest in Scandinavia as a political and cultural entity.

While it’s certainly true that a rivalry still exists between Denmark and Sweden, it’s now more the kind experienced by siblings.

Sweden might remain the country the Danes love to hate, but it’s all pretty amiable now – although it’s fair to say there’s been a fair bit of grumbling since Sweden decided to close its borders – even though some may have longer memories than others.