Business & Education

A bestseller across the world, and even in Denmark … after a few tweaks

This article is more than 9 years old.

How a Danish part-time poet decided to improve the classic children’s book ‘Der Struwwelpeter’ by binning three of its ten stories and adding three of his own

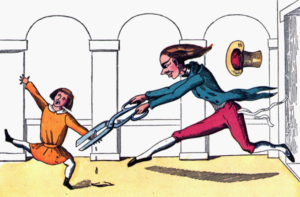

Mamma had scarcely turn’d her back/ The thumb was in, Alack! Alack! (photo: Heinrich Hoffmann (1809–1894))

The worldwide success of the German children’s book ‘Der Struwwelpeter’ has baffled many since its release in 1845. Its ten short story poems about children who test good behaviour boundaries and are punished for their misdemeanours, often with death, was aimed at the three to six-year-old market – a readership incapable of appreciating its rich irony. But yet it has sold millions and is today still regarded as one of the classics of our time.

But in Denmark, a second mystery endures. When the book was translated into Danish and published in 1847, three of the stories were removed and replaced by three new ones. Did the writer, Simon Simonsen, a part-time poet and party compère, regard those stories as distasteful or perhaps inferior, or did he simply think that his additions were too good to not include?

Grimm by nature alright

Today few people associate children’s stories with horror and irony, but back in the day this was the norm, and in many ways ‘Der Struwwelpeter’ was simply following tradition. While today’s movie studio conglomerates have Disneyfied most original children’s stories, the original fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm, for example, were essentially folk stories about dangerous animals, trolls and witches that eat children – of which ‘Hansel and Gretel’ is a good example.

‘Der Struwwelpeter’, therefore, is a little like the original Grimm tales, but with unhappily ever after endings. The consequences of the children’s crimes are alarming: they lose limbs, are burned alive and often die – and it’s all described in graphic, often amusing detail. It’s enough to give the hardiest of children haunting nightmares.

The moral of this story is … err

The book was conceived by a doctor of all people. Heinrich Hoffman (1809-1894) wrote it for his three-year-old son as a critique of contemporary German society’s tendency to excessively moralise in children’s literature.

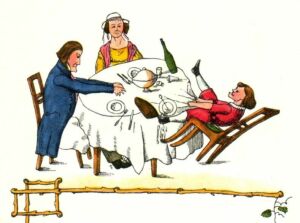

It is therefore a little ironic to note that it is exactly this sort of moralising that Simonsen indulges in. In Hoffman’s stories, the children misbehave. They lean back on their chairs, don’t look where they’re going, go outside in a storm, are scruffy, suck their thumbs, play with matches, are fussy eaters and are cruel to animals.

But in Simonsen’s stories, which were originally published in 1847 as ‘Vær lydig, eller lystige Historier og moersomme Billeder for Börn imellem 3-6 Aar’ (Be obedient, or merry stories and funny pictures for children between 3-6 years old), the children are sinful, and the message is quite clear: if you’re envious, greedy or vain, this will happen to you.

Down upon the ground they fall / Glasses, plates, knives, forks and all (photo: Heinrich Hoffmann (1809–1894))

A cock lands on her face

In ‘Historien om Spejldukken’ (the story of the mirror doll), a vain girl looks in the mirror too much and ends up with a crooked mouth when the wind changes direction – not via the traditional method, but when the weather cock falls off the roof and lands on her face.

In ‘Historien om Hanne i Maanen’ (the story of Hanne in the Moon) an envious girl wants to own everything she sees, including the moon, whose reflection she sees in a lake – she drowns trying to get it and ends up becoming the Woman in the Moon.

And in ‘Historien om Rikke Slikmund’ (the story of Rikke with the sweet tooth), a greedy girl with a teeth tooth who ends up eating insect poison and getting a sore nose.

Omissions and a new cover boy

To make room, Simonsen removed the story of the wild huntsman. According to Torben Weinreich, a professor of children’s literature, Simonsen couldn’t see the moralistic merit in the only one of Hoffman’s stories to depict a misbehaving adult: a huntsman whose gun is picked up by a hare who shoots back, causing the huntsman to jump in a well and the huntsman’s wife to drop her coffee cup and scald one of the hare’s children. The story is pure nonsense poetry, not dissimilar to the work of Edward Lear, whose breakthrough book, ‘A Book of Nonsense’, came out in 1846.

And Simonsen also mysteriously removed the last two stories of ‘Der Struwwelpeter’: The Story of Johnny Head-in-Air’ (look where you’re going) and ‘The Story of the Flying Robert’ (Don’t go outside in a storm).

There are also other changes, most notably the decision to cast another character as the title character of the whole book. In German, Struwwelpeter, a short poem about a scruffy boy who does not comb his hair or clip his nails, translates into scarecrow, and in the English version, the translators were happy to keep this as the title, but named the character ‘Shock-headed Peter’, which became the name of a successful 1998 stage production of the book, written by the cult band The Tiger Lillies.

But for the second edition of his Danish version (the original German book also had a convoluted title), Simonsen decided that the Danish translation of Struwwelpeter was misleading and not catchy enough, and he promoted Den Store Bastian (the great Bastian), the central character of ‘Historien om de sorte drenge’ (The story of the black boys), to the frontpage.

Bad-ass Bastian bashes the bigots

And it is this story that Simonsen changes the most, instilling the language with the moral undertone that Hoffmann distanced himself from, although the storyline is pretty much the same: Bastian (in the original St Nicholas, and in the English version, Agrippa), who is clearly a summertime version of the Father Christmas who used to bring gifts to the homes of the good children but spank the naughty children, reprimands three racists in Vesterbro for taunting a passing black boy (Simonsen uses a different term, of course, but it was the 1840s) and plunges them into a giant inkwell.

Funnily enough, two well-known Danish authors, Flemming Quist Møller and Rune T Kidde, adapted the book in 1992 to depict misbehaving adults, returning the irony to the subject matter that the moralistic Simonsen had done his best to eradicate in his translation.